A well-known writer produces poetry and other works in his lifetime. When he dies, what has been left unpublished is far more than what has been. His son becomes his literary executor. Not only does he make sure the unknown works are published; he also heightens his father’s literary standing in the process. Whom does this describe?

If you said this is J.R.R. Tolkien and his son Christopher, you would be right. If you said Geoffrey Chaucer and his son Thomas, you would also be right. We know far more about J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary achievements because of his son Christopher. And we have Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and other works because of his son Thomas.

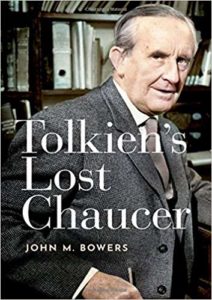

Bowers’ work is about a book that was never actually written. In 1922, while at the university of Leeds, Tolkien was contracted by Oxford University Press to co-edit and publish a Clarendon Press student edition of selections of Chaucer’s poetry and prose. His fellow contractor was George Gordon, Professor of English Literature at Merton College, Oxford. Gordon, who was not a Chaucer specialist, would serve as senior editor, assigned to write the introduction and testimonials. Tolkien, as junior editor, would provide the glossary and notes.

Gordon was a procrastinator, usually involved in many other things, including teaching and college administration. Tolkien was also something of a procrastinator, but he did have a young and growing family and overlapping university assignments with Leeds and Oxford in 1924/25. But both accepted the contract and set about producing the book.

As it turned out, Tolkien accomplished far more than Gordon, but even Tolkien never finished. Other work beckoned. Including his university duties, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings. The work continued off an on the Chaucer book for years, almost 30 years, in fact, and even survived Gordon’s death in 1942.

Geoffrey Chaucer

Finally, in 1951, the editor of Oxford University Press had had enough of the delay, and asked Tolkien for all the papers related to the Chaucer volume. Tolkien complied and sent the material in a box. For a time, it looked as if another editor might complete the student edition. But that ultimately never happened. Tolkien’s and Gordon’s papers were shelved at the publisher’s office. Eventually they found their way to the basement of the Bodleian Library.

And there they sat, until 2012, when they were almost accidentally discovered. Even Christopher Tolkien was unaware of the rather extensive work his father had done on Chaucer. The manuscript was more complete that many of Tolkien’s other manuscripts that Christopher had edited and published after his father’s death in 1973.

Yet there were hints. Tolkien gave a series of lectures on Chaucer in the late 1930s (including dressing in costume), and the talks didn’t materialize out of thin air. In 1945, Tolkien became Merton College Professor of Language and Literature. That required lectures on Chaucer. It was clear he had an extensive background in Chaucer, greater than simply a basic familiarity or cursory reading. But the manuscript with his meticulous and extensive notes gathered dust.

Bowers came to Tolkien relatively late, and he didn’t even read the LOTR trilogy until the Peter Jackson movies began in 2001. Once he did, and later, once he studied the Chaucer manuscript, he realized how much influence Chaucer had had on Tolkien’s writings. And it’s all included in his book.

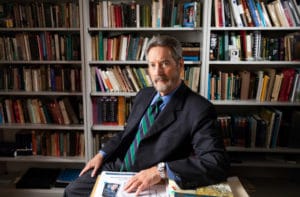

John Bowers

A specialist in medieval English literature at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, Bowers is also the author of An Introduction to the Gawain Poet, End of Story: A Novel, Chaucer and Langland: The Antagonistic Tradition, The Crisis of Will in Piers Plowman, and The Politics of Pearl: Court Poetry in the Age of Richard II. He received degrees from Duke University, University of Virginia, and Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Guggenheim Foundation.

Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer is an engrossing work in its own right. But it also adds significantly to our understanding of the life and work of one of the most important authors of the 20th century.

Related:

Editor of the “Legendarium:” Christopher Tolkien (1924-2020)

The Abounding Creativity of Middle-Earth: An Appreciation of J.R.R. Tolkien

The Last of the Tolkien Tales: “The Fall of Gondolin”

A New Exhibition: Tolkien and the Making of Middle-earth

“The Fall of Arthur” by J.R.R. Tolkien

Tales of the First Age: “Beren and Luthien” by J.R.R. Tolkien

“The Children of Hurin” and “The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun” by J.R.R. Tolkien

Poets and Poems: J.R.R. Tolkien and “Beowulf”

Photo by Simon Harrod, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Beth Copeland and “I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart” - July 10, 2025

- A.E. Stallings: the Parthenon Marbles, Poets, and Artists - July 8, 2025

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

Bethany R. says

Interesting (and relatable in a tiny way) to think of all those hours Tolkein spent working on his Chaucer writing, that we may not have ever known about. For every well-loved, well-known book, how many more potential books have been written or almost written, but are still unknown? Thanks for this post.

Will Willingham says

Not that the “well-known writer” part would be an issue (lol), but remind me to make sure my kids understand they are not to be publishing anything they happen to rustle up when they clean out my house one day.

Glynn says

Ha! Perhaps we should invite Marie Kondo to take a look at our archives and files!