Frank Stanford was born in Mississippi in 1948, and adopted the day he was born. Four years later, his mother married A.F. Stanford, a much older contractor in Memphis. Until his death eight years later, Stanford raised the young boy as his own. When he was 21, Frank discovered that his mother had adopted him—he had always believed, or been led to believe, that she was his birth mother.

We can smile at William Wordsworth’s line “The Child is father of the Man, ” but poet Frank Stanford embodied it in both his life and his poetry.

I discovered Stanford while reading poet Leon Stokesbury’s most recent collection You are Here. Stokesbury teaches in the creative writing program at Georgia State University, and received his M.A. and MFA degrees from the University of Arkansas, and there is his connection to Stanford. Stanford and his mother moved to Arkansas after his stepfather’s death, and in 1966 he entered the University of Arkansas. He was enrolled in the university’s graduate poetry workshop at the same time Stokesbury was in the MFA program.

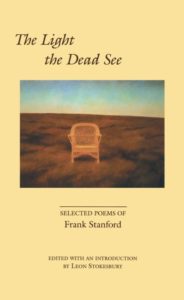

“Almost from the beginning there was a unique voice in the poems Stanford submitted to the workshop, ” Stokesbury writes in the introduction to The Light the Dead See: Selected Poems of Frank Stanford edited by Stokesbury and published in 1991. Between Stanford’s death in 1978 and a comprehensive collection of his poetry published in 2015, the Stokesbury-edited work was the only extended publication of Stanford’s poems.

What Stokesbury did was select a poem from each of the seven collections of poetry Stanford published from 1971 to 1978 (think about that for a moment—seven collections in seven years). Most of Stanford’s poems were still unpublished at the time of his death, and Stokesbury did manage to include a few.

The poems of The Light the Dead See are, simply put, rather astonishing. They tell stories. They are filled with striking imagery. I find many of them so memorable as to be haunting. As I read the poems I kept thinking of Flannery O’Connor and her Southern vision of the odd, the misfits, and the strange. Stanford’s images and stories demand attention and engagement.

His subject was mostly childhood, and particularly the childhood spent growing up in a Southern community at a time when the South was on the brink of tumultuous change. He writes of childhood memories viewed through an adult lens, memories recalled with a grasp that is fond and loving but also understanding and at times shocking. Much of his poetry is about growing up in the 1950s South.

A girl was in a wheelchair on her porch

And wasps were swarming in the cornice

She had just washed her hair

When she took it down she combed it

She could see

Just like I could

The one star under the rafter

Quivering like a knife in the creek

She was thin

And she made me think

Of music singing to itself

Like someone putting a dulcimer in a case

And walking off with a stranger

To lie down and drink in the dark

Stanford ‘s personal life was rather tumultuous, Stokesbury notes. He married young, divorced, married a second time to painter Ginny Crouch. He was publishing poems and collections all through his 20s, and even joined with poet C.D. Wright (who died earlier this year) in launching a firm, Lost Roads Publishing, devoted to poetry. His biography reads like a man burning the candle at both ends, and, alas, that is apparently what happened.

He died just short of his 30th birthday. Stanford killed himself with three gunshot wounds to the chest. Stokesbury speculates that the reason was something of a poetical inspiration crisis—doubts that he had anything left in him to write about.

This poem is perhaps his best known, obviously for how it can be read as a foreshadowing of his death.

Frank Stanford

The Light the Dead See

There are many people who come back

After the doctor has smoothed the sheet

Around their body

And left the room to make his call.

They die but they live.

They are called the dead who lived through their deaths,

And among my people

They are considered wise and honest.

They float out of their bodies

And light on the ceiling like a moth,

Watching the efforts of everyone around them.

The voices and the images of the living

Fade away.

A roar sucks them under

The wheels of a darkness without pain.

Off in the distance

There is someone

Like a signalman swinging a lantern.

The light grows, a white flower.

It becomes very intense, like music.

They see the faces of those they loved,

The truly dead who speak kindly.

They see their father sitting in a field.

The harvest is over and his cane chair is mended.

There is a towel around his neck,

The odor of bay rum.

Then they see their mother

Standing behind him with a pair of shears.

The wind is blowing.

She is cutting his hair.

The dead have told these stories

To the living.

Largely forgotten except for Stokesbury’s book, Stanford is enjoying something of a revival. Last year, The Collected Poems of Frank Stanford was published, edited by Michael Wiegers. It includes both published and unpublished poems.

The Light the Dead See is a fine introduction to the larger and more recent collection. It’s no longer in print but can be found through Amazon’s sellers of used books (I bought a copy in almost brand-new condition for $3.99 and shipping).

Stanford deserves to be better known. He wrote powerful, memorable poems.

Related:

Oxford American: The Last Panther of the Ozarks.

A dramatic reading of “The Light the Dead Can See:”

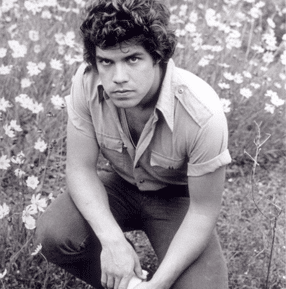

Photo by Eduadro Mineo, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Beth Copeland and “I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart” - July 10, 2025

- A.E. Stallings: the Parthenon Marbles, Poets, and Artists - July 8, 2025

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

Mary Harwell Sayler says

Glynn, thanks for continuing to introduce us to gifted poets whose work we might never see without your spotlight on them. God bless.

Glynn says

Thanks, Mary! Stanford is one of those poets who could have easily slipped into obscurity.

L.L. Barkat says

I especially like:

“And she made me think

Of music singing to itself”

And in that last poem the particular images of father and mother seem to pull together a long grief. Yes, haunting.

Glynn says

It was as if the child in him is still looking for his parents. In the introduction, Stokesbury wonders if his suicide might have been tied to his belief that he had exhausted his childhood memories and couldn’t find inspiration anywhere else.

L.L. Barkat says

Fascinating evaluation. Yes, at least this poem gives that sense of mourning—and yet maybe also a sense that he wanted to take what he had left image-wise with him (an undeniably strong series of pictures of them to hold, frozen in time in a poem like this one).

Bethany says

I liked those lines too, L.L. 🙂

Maureen says

An important poet who, like many others, died too young. Look at the intensity in his eyes in the photo you’ve included here.

Stanford’s similes in that first poem (“a star … / quivering like a knife in the creek”) are so sharp (no pun intended), and balanced by the lyricism of lines like “She had just washed her hair / ….” Beautiful.

The imagery in the second narrative poem is gripping.

Glynn says

All of his poetry is like that. Thanks for the comment, Maureen

Bethany R. says

Yes, this image in this line stuck with me: “The harvest is over and his cane chair is mended.”

Bethany R. says

I’m struck by “The Light the Dead See.” Interesting how he overlapped the senses in:

“The light grows, a white flower.

It becomes very intense, like music.”

And I can still see the signalman swinging the lantern, and the mended cane chair.

Glynn says

The words often grab you by the throat. He has some wonderful lines. Thanks, Bethany!

SimplyDarlene says

Wow. It’s not much like reading words, but rather like leaning one’s head to his chest as memories thrum straight through.

“There is a towel around his neck // The odor of bay rum” <– that bit won't leave me alone.

Glynn – as always, thanks for teaching, sharing, and conversing.

Glynn says

Thanks for commenting, Darlene!