I’m reading On Balance, the newest collection by poet Sinead Morrissey, and for some odd reason, I keep being reminded of Brooklyn Bridge. It’s not that Morrissey’s collection is influenced by other poets who wrote about the bridge—Hart Crane, Jack Kerouac, and Marianne Moore among them. It’s more that the poems of this collection grapple with technology, the wonders technology brings, and the tradeoffs that technology always demands. I’m reminded, too, of the French Impressionist painters like Renoir who painted pastoral scenes with railway bridges and trains in the background (or foreground).

Morrissey lives in Belfast. Possibly the most famous ship ever constructed in the famous shipyards there was the Titanic, so it’s not a surprise to find the first poem (and the first about technology) in On Balance is about the doomed ship. Specifically, “The Millihelen” focuses on the moment the ship travels down the slipway into the water. It represents a marvelous feat of human engineering, and one that will eventually cost the lives of more than 1,500 people. Technology has its price.

The poems may address the telegraph, the cinema, coal mining, war, and even color photographs of tsarist Russia, but Morrissey is always reminding us of technology and its costs, and the disequilibrium it can cause with the natural world. This is true even for something like a scientific expedition to Greenland, possible only because of technology, which is fully represented by the participants—a geologist, a photographer, an artist, a marine biologist, and an archaeologist. In a series of poems under the general title of “Whitelessness,” Morrissey gives each participant a soliloquy.

This is the first in that series, “The Geologist”:

This one’s a fossilised algal mat; this one

contains the ridges of human teeth:

some early Paleolithic adolescent caught

grinning at the moment of death

in a stone photograph. We manoeuvre

them down to the beach on a stretcher.

Ochres and greys and blacks

ricochet back and forth across the massif,

as denuded of white as the West of Ireland,

while the shed ice bobs in the bay

begging smaller and smaller comparisons—

lozenges dissolving visibly on the tongue;

droplets of fat on broth. If it’s life

that controls the geological machinery

of the planet, rather than the other way round,

we are neither new, nor tragic. This came

to me one morning as I sorted out my cabin

and the hundreds of marathon runners

in my brain stopped and changed direction.

Sinead Morrissey

The italicized words in the poem are they key, and Morrissey plays two ideas almost in reverse of what might be expected. “Life” is what brings technology; “the geological machinery” actually represents the natural world. She is perhaps suggesting here that we see technology as the natural thing, and nature as something to be controlled and regulated.

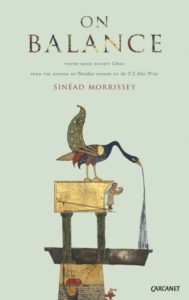

Morrissey has published five other poetry collections: There Was Fire in Vancouver (1996); Between Here and There (2002); State of the Prisons (2005); Through the Square Window (2010); and Parallax: And Selected Poems (2015), which won the T.S. Eliot Prize. On Balance won the Forward Prize for poetry earlier this year. She received her B.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Trinity College Dublin, and was named Belfast’s first poet laureate in 2014.

On Balance is not a screed against technology. But it is a reminder that, like Prometheus and his theft of fire, technology brings the good, the bad, and the unexpected.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Hart Crane, “The Bridge,” and Me

Photo by Diane Rosete, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Beth Copeland and “I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart” - July 10, 2025

- A.E. Stallings: the Parthenon Marbles, Poets, and Artists - July 8, 2025

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

Marvelous sample poem, which I am still puzzling through. 🙂

The opening and the ending seem at odds. In the opening, the stones brought the death of someone in the prime of life. So it seems that the stones are the center of the “machine.”

But then, it is the” fossilised algal mat” and “the ridges of human teeth” that has made the stone, in part. And this life-in-death is now being “manoeuvre[d]…down to the beach on a stretcher”—an image of rescue (less than control, I think).

So the real question is what new direction did the marathon runners in her brain take?

Something to do with “we are neither new, nor tragic,” seems plausible. Something, perhaps, like an illumination that even when we move things around, treat the stones like something to be rescued, we are not in control. We are part of the whole. And, in being part of the whole, this makes us not new and not tragic—perhaps taking the pressure off our racing selves.

Bethany R. says

What a fascinating post and featured poem. I’m also still thinking through it, L.L. 🙂 Yes, what new direction did the marathon runners in her brain take? What a great image for the forever-active thoughts we work with through the years—and what it’s like to shift perspectives (at least that’s how I absorb it).

Just brainstorming here – for me, so much is tied up in that fossil containing “the ridges of human teeth” and the idea that the subject is “grinning at the moment of death”. Was she? The first thing I thought of there, was that this poor soul probably needed something to bear down on as she suffered in her last days. But I juxtapose that with the poet’s idea that “…we are neither new, nor tragic.” Was this person the victim in a bigger, older, natural world that she has no chance against? Or did they have some kind of control, and were leaving their mark?

The title is interesting too.

Sandra Heska King says

Whitelessness. I had to stop to think about that word. There is a Whiteless Pike in England’s Lake District that apparently appeared in some of Wordsworth’s and Beatrix Potter writings. Then I went down a rabbit hole exploring the color “white.”

So many metaphors in this poem to savor. And I love the “This came to me one morning . . .” And then the marathon runners change direction.

Bethany R. says

Interesting about that area of the Lake District and how Wordsworth and Potter mention them, Sandra. I’m glad you looked “whitelessness” up and shared this.