Poet Mai Der Vang was born and grew up in Fresno, California. As she describes in the Spring / Summer issue of American Poets Magazine, she was about 10 years old when she wandered into her uncle’s house to look at his books. And there on a shelf, among the textbooks he was using for his courses in mechanics at a local community college, were several National Geographic magazines dating back to the 1960s. The issues had one thing in common: stories about the Hmong people of Southeast Asia.

For Vang, it was a life-changing event. She discovered where she came from. And she would also discover where she was going. And her discovery would lead her to poetry and other literary writing and the Walt Whitman Award.

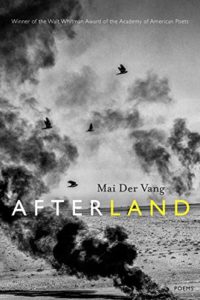

Afterland is Vang’s first collection of poems, and many if not all of its 57 poems are about the Hmong people. They live (and lived) in southeastern China, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand. During the Vietnam War, thousands were recruited by the CIA to fight both the North Vietnamese and the communist Pathet Lao. Without U.S. support and protection, the Hmong would find themselves especially vulnerable.

In 1975, when the United States abandoned southeast Asia and the communists took control, the Hmong began to flee, knowing the reprisals would be forthcoming. They left any way they could find, and thousands swam with their families across the Mekong River to reach safety in Thailand. Many did not make it across the river. Here’s is Vang’s poetic translation of that event.

Water Grave

the midnight shield

and learn that bullets

can curse the air.

A symposium

of endangered stars

evicts itself to

the water. Another

convoy leaves the kiln.

The crowded dead

turn into the earth’s

unfolded bed sheet.

We drift near banks,

creatures of the Mekong,

heads bobbing like

ghosts without bodies,

toward the farthest shore.

With every treading

soak, the wading leg,

we beg ourselves to live,

to float the mortared

cartilage and burial

tissue in this river yard

of amputated hearts.

Vang writes of burning towns, migration, refugees, war, and survival. The last poem in the collection is the title poem, and it is a bringing together of history and hope. All of the poems are moving and haunting, pricking our collective memory of the war and reminding us that the people who helped the American war effort often turned out to be the most vulnerable when that effort failed. And yet these are not the poems of “victims,” but rather poetry that points to a people’s resilience in the face of war, loss, displacement and exile.

Mai Der Vang

Afterland was awarded the 2016 Walt Whitman Award by the Academy of American Poets, given for first poetry collections. The award includes a $5,000 cash award, a six-week residency at the Civitella Ranieri Center in Umbria, Italy, and distribution of the book to the members of the Academy. That distribution, underway this spring, almost guarantees that it will be one of the most read books of poetry of the year.

Vang’s poems have appeared in numerous literary journals and magazines, including The Missouri Review Online, The Cincinnati Review, The Asian American Literary Review, The New Republic, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. She received a B.A. degree in English from the University of California-Berkeley and an MFA degree in Creative Writing / Poetry from Columbia University. She lives in Fresno.

Vang notes in the American Poets WHICH? article that the Hmong people had no written language until the 1950s. At that time, American missionaries arrived in the region, and to preach to the Hmong, they developed a language based on the Roman alphabet, which continues to be the primary written language of the Hmong people today. She is an editorial member of the Hmong American Writers Circle, founded in 2004 to “discover and foster creative writing among the Hmong people,” and co-edited How Do I Begin: A Hmong-American Literary Anthology (2011).

Afterland is a collection of poems about a people’s past, but a past that never really remained there. It has carried forward into the present and the future, and the poetry of Mai Der Vang will help ensure its place in literature.

Photo by Neal Fowler, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

Megan Willome says

My uncle served in Vietnam in a then-secret group of pilots called the Ravens. They continue to be involved with Hmong-American communities in the States, feeling they have an obligation to these people that our government did not fulfill. They raise money for scholarships every year.

Bethany R. says

Wow Megan, it sounds like your uncle and his group are quite committed to contributing to these communities. Scholarships can have such far-reaching positive affects, I’m glad you shared this.

Glynn says

So much about the Vietnam War was almost intentionally forgotten. Poetry, like this collection, is one way it can be remembered.

Maureen says

I also read ‘Afterland’ recently. While I found it indeed praise-worthy, especially its strong and often remarkable imagery, I found myself tiring of Mai Der Vang’s diction – her frequent use of words (nouns especially) as other than intended (e.g., cathedral as a verb).

Sandra Heska King says

Who knows where a National Geographic Magazine can take you…

Interesting that the Hmong had no written language until the 1950s–and then how it came to be.

Bethany R. says

I was struck by that too, Sandra, as well as Glynn’s comment that, “…yet these are not the poems of ‘victims,’ but rather poetry that points to a people’s resilience in the face of war, loss, displacement and exile.” Sounds sobering and inspiring.

Sandra Heska King says

Yes. That, too.

Katie says

Glynn, Once again – thank you for bringing us a poet whose work needs to be read. I have cousins who served in Vietnam who still cannot talk about it to this day. So thankful that my older brother was never called up.

“For Vang it was a life-changing event. She discovered where she came from. And she would discover where she was going.”

“Afterland” is a collection of poems about a people’s past, but a past that never really remained there. It has carried forward into the present and the future, and the poetry of Mai Der Vang will help ensure its place in literature.”

Two superbly crafted paragraphs.

Gratefully,

Katie

Glynn says

Katie – thanks for the comment!