Stephen Cushman mixes the secular and the sacred

I’ve been reading about the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness, fought largely amid dense trees and shrubs north of Richmond, Virginia. Weather conditions had been dry the spring of 1864, and the artillery fire ignited the brush. Horrific conditions resulted. Many men burned to death; others barely made it out of the line of fire. It was the first military confrontation between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, and neither man was going to budge.

One of the books I was reading was Bloody Promenade by Stephen Cushman. It’s less of a historical account and more a reflection upon the battle itself. Cushman lives and teaches not far away, in Charlottesville, Virginia, and he’s been long fascinated with the Civil War in general and that battle in particular.

He’s also a poet. When I read his book jacket biography, his name sounded familiar. Later, I saw his list of poetry collections, and I realized I had reviewed one of them, Riffraff: Poems, here at Tweetspeak.

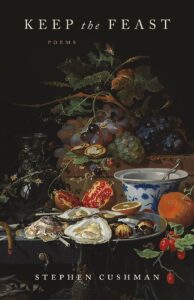

His latest collection, Keep the Feast, was published last year. In an odd way, I’m glad I read Bloody Promenade first. It was published almost 25 years ago, but I can see how the poet who reflected on a terrible, tragic Civil War battle would write the kinds of poems that comp0se Keep the Feast.

The poems are a combination of the secular and the sacred. Some of the included poems are both. They read like psalms. A sense of reverence characterizes them, whether they are about the garden of Gethsemane or an employee in the mailroom. The poems are initially rather jarring; have you ever been advised to love your neighbor as your self-portrait? Or visit a scene like Dealey Plaza, the site where President Kennedy was assassinated during his Dallas motorcade? Or perhaps to include a poem describing a casserole for the bereaved?

And then you read a contemporary version of a famous and familiar scene.

No Counting Sheep Without Feeding Them Too

may prompt referral

to laboratory overnights

(Polysomnography,

would you look on me,

electrodes attached?),

and wee-hour waking may be a sign

of depression, it says,

but what could depress

when neither son of Zebedee

needed hypnotics, white ones like these

approved by the Air Force

in support of mission readiness,

to help them blow z’s

through the garden where an oil press

explains the name Gethsemane,

where someone gone cold turkey

on this last night, before arrest,

could easily watch with thee.

I have to catch my breath after that one. Even the hotheaded brothers fell sound asleep, right on the verge of their world coming to a radical end.

Stephen Cushman

The heart of the collection is the title poem, “Keep the Feast.” Its 26 stanzas each begin with a letter of the alphabet (don’t ask where I was when I figured that out (the stanza beginning with “p,” if you must know)). The imagery of this long poem overflows with sacred and secular references, sometimes in the same lines. You read a poem like this, and you see this is the life we live, in all its glory, tragedy, happiness, depression, rich fullness, and often shocking emptiness.

Cushman is the Robert C. Taylor Professor of English at the University of Virginia. He’s published seven poetry collections, including Keep the Feast, and two books of poetry criticism, on poetic form and William Carlos Williams. He’s also published three books about the Civil War: The Generals’ Civil War: What Their Memoirs Can Teach Us; Belligerent Muse: Five Northern Writers and How They Shaped Our Understanding of the Civil War; and Bloody Promenade: Reflections on a Civil War Battle.

Reading Keep the Feast is accepting something of a challenge. It’s as if Cushman is daring you to try to separate the sacred and the profane. Try as you might, it can’t be done.

Related:

Photo by Mark, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

Leave a Reply