It is strange to read A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1812-1870) and see the ongoing media coverage of Charlottesville, controversies over and vandalism of Confederate monuments, and the divisions in American society becoming only sharper. I say “strange” because the story that Dickens tells is a reminder that despite our science, our technology, our educational attainments, and the growth of knowledge, our human condition remains stubbornly the same.

The first and last time I read the book was in my sophomore year of high school. Our English class dutifully carried around the paperback edition published by Dell (the publisher, not the computer maker) with a yellow-orange cover. It’s one of Dickens’s shorter works, but to 10th grade boys, it still looked like a lot of fat book to read. Some in our class found the Cliffs Notes version of the book, while others got their hands on the Classics Illustrated comic book edition. A few of us read the book itself.

The story has only four main characters. Dr. Alexander Manette, a Parisian physician, is falsely imprisoned to cover up a crime committed by members of the nobility. He nearly loses his mind during the long years in prison. His daughter, Lucy Manette, is brought up in England. Charles Darnay, a Frenchman, has emigrated to England to make his own living, having rejected his noble Evremont family for their cruelty and general wickedness. And Sydney Carton, an Englishman who is no relation to Darnay but looks remarkably like him, works various odd jobs in London’s court system as he drinks himself to death.

The story begins years before the French Revolution starts in 1789 with the attack on and fall of the hated Bastille prison in Paris. Dickens tells the story with the sense of inevitability—the storm that is coming upon France has been building for a long time.

The book contains two of the most quoted passages in English literature—the opening (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”) and the closing (“It is a far, far better thing I do …”). And while the two cities are ostensibly London and Paris—both of which displayed a horrendous disparity in wealth and social class—what the cities ultimately represent are choices.

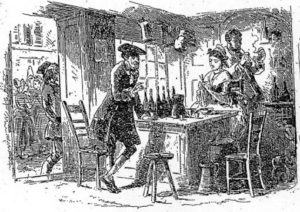

Madame Defarge int he wine shop, by Hablot Knight Browne, aka “Phiz”

Dickens’s genius for characterization extends to his minor characters. Miss Pross, for example, is the English companion who helps to raise Lucy Manette, and she is about as quintessentially English as they come. And Madame Defarge, who sits silently click-clicking her knitting needles, sewing the names of the those who must die into her work, still provides chills.

For research, Dickens used one of the most popular histories of the 19th century, The French Revolution: A History, published in 1837 by Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881). Carlyle wrote more than the story of the revolution and the Reign of Terror that followed; he also captured the horror of the English middle and upper classes at the grotesque and murderous excesses that became everyday life in France for a time. It wasn’t only the nobility and the king and queen who went to the guillotine; the thirst for vengeance became so out of control that anyone, including tens of thousands of innocent people, could be accused, sentenced, and executed. It would only stop when the Terror began to consume itself, and the military, led by Napoleon, took over.

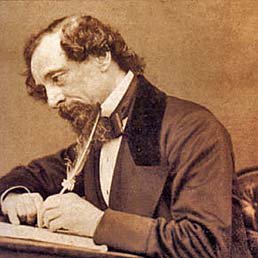

Charles Dickens

It’s not difficult to see from the book where Dickens’s own sympathies were—clearly on the side of law and order. But he wasn’t so insensible not to understand what had caused the revolution—generations of deprivation, want, and taxation for the lower classes, while the nobility wasted itself on frivolity, entertainment, cruelty, and excess. We eventually learn why Madame Defarge was filled with so much hate and anger, and we understand it. When the storm finally broke, however, it wasn’t only those most at fault who were swept away.

While the conditions faced in our country are nothing like what had happened in France, A Tale of Two Cities can be read as a morality tale, and a lesson on what happens when injustice is allowed to fester, and when the explosion leads to horrible excess.

Related:

“David Copperfield”: Why Charles Dickens Has Endured

The Surprise of “Oliver Twist” by Charles Dickens

Photo by Nick Amoscato, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Beth Copeland and “I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart” - July 10, 2025

- A.E. Stallings: the Parthenon Marbles, Poets, and Artists - July 8, 2025

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

Bethany says

I haven’t read this since high school, but remember the story gripping me (minus a scene about playing cards, which at the time I had to keep rereading to absorb). I felt quite emotional when I finished the last page of that book.

Interesting point about it being a “lesson on what happens when injustice is allowed to fester, and when the explosion leads to horrible excess.”

Rick Maxson says

I had the same reaction to this book as you, Glynn—pages to get through. It wasn’t until my reading of A Tale of Two Cities for a sociology class in college that I appreciated its language, sense of place, and characterization. The professors who taught the course first gave a week long presentation (in costume) of life and politics during the time of which Dickens wrote. That was decades ago and I still vividly recall much of that class, which was responsible for Dickens being one of my favorite authors.

I often wonder how many lessons humanity must create and then reflect on before we learn how alike we all are, rather than insisting we first cater to our differences in politics, class, religion, and status. In her book The Lord and the General Din of the World Jane Mead asks, should we choose to live, and if so, how do we go about it? What far better things should we do than we have ever done before? And what far better rest will we deserve, having done so?

Bethany R. says

How wonderful that your professors presented in costume–it certainly did stick with you.

“I often wonder how many lessons humanity must create and then reflect on before we learn how alike we all are…” Yes.

Those are substantial questions that Jane Mead raises. Now you’ve got me thinking.

L.L. Barkat says

Now… I almost want to read this book! 😉 I like your quick retelling of it and might be satisfied just with that.

Also, it reminds me of the excellent handling of the particular French Revolution you’re discussing, in the book Stoned—where you can also discover that Marie Antoinette was misquoted about the cake and, by that time in her life, was actually asking the crown to spend more money on the people, and she was funding charities… but PR wasn’t her deal and it was the end of her, in the end, when she was framed for a diamond necklace debacle.

Bethany R. says

“I almost want to read this book!” Ha! I love that you only read what you wish to, L.L. 😉

Interesting note about Marie Antoinette in the book “Stoned.”

Monica Sharman says

Thanks for showing us another Dickens novel, Glynn. This one is in my top three favorite books (and the only of the three not written in French, but all three are deeply involved in French history — interesting). The first time I tried reading it was when it was assigned in high school. Never got past the first two paragraphs. Then I picked it up in my thirties. A decade and a half can do a lot to a reader, I guess.

I’ve been wanting to read that Carlyle history. Maybe now is the time.

Oh, and you might have opened a can of worms with this: “And it is a major reason why his later novels remain some of the most powerful works in literature—he knew from the beginning where the story was going to end.” Sounds like something that can spark a heated debate between plotters and pantsers (those who write by the seat of their pants)! 😉

Michele Morin says

I have such a weak background in classic literature. This sounds like a great place to begin in turning that around.