Our Keats Walk in Hampstead in north London, led by guide Anita Miller, has brought us to Hampstead Heath. Our first time on the Heath was a week before, when we visited Kenwood House on the north side of the Heath and the place occupied by the various earls of Mansfield (and the setting for the 2013 movie “Belle, ” which is well worth seeing). The house includes an incredibly fine art collection, including a Rembrandt, a Vermeer, some Constables, a Gainsborough or two, a Van Dyck, and many others.

Today we’re on the south side of the Heath (and it’s a big heath). We have just crossed the street from Well Walk and entered what is a forested part of the area.

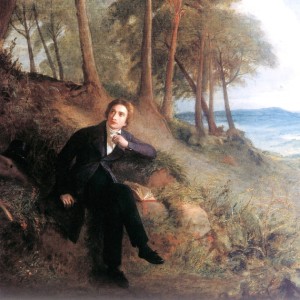

This is a place John Keats knew well. He would often walk from where he lived on Well Walk across part of the heath to Wentworth House, where his good friend Charles Armitage Brown lived. Brown was the companion who spent 48 days hiking Scotland with Keats, and the friend who would offer Keats a place to live after his brother Tom died in late 1818.

This particular part of the Heath is where Keats would walk with his fiancée Fanny Brawne. The path likely wasn’t the canopied walkway we see today, but that is an afterthought as we stop and listen to Anita read from a letter Keats wrote to Brawne. The setting makes the words seem much more alive than simply reading them on a page.

I’ve seen the Heath numerous times on British television shows, usually crime dramas—the Heath is a good place to dump a body and it has sweeping vistas of the London skyline. It has a history dating back to Ethelred the Unready in 986; since 1989, it’s been managed by the City of London Corporation. The Heath includes an important conservation district, and it is surprising to find so large a space of undeveloped “common land” in a city the size of London.

From the pathway, we scramble up a small hill and we’re suddenly in what looks like a “heath” in our imaginations—a vast tract of open land, with field flowers and short grasses and the occasional clump of trees. We walk in the direction that Keats would have walked from Wall Walk to Wentworth House, and suddenly Anita veers off the rutted trail and leads us to a large tree with low hanging branches. The tree isn’t connected to Keats, but it’s here that she chooses to tell us the story of Keats’ illness, decline and death in Rome.

Consumption, or tuberculosis, ran in Keats’ family. His mother and youngest brother Tom died from it, as did other family members. It was a common disease at the time, and its diagnosis was a death warrant—there was no cure. Sun and warmth seemed to help, but that’s not the common weather of Britain.

Tom Keats was in serious decline with the disease when John headed off to Scotland with Charles Brown. Keats came home from the trip earlier than expected—he had developed a sore throat he couldn’t shake. While on his way home by ship, a letter headed north missed him, telling him that Tom was in dire shape. Keats nursed his brother until his death in December 1818, and undoubtedly breathed in the same tuberculosis air that Tom was breathing out.

After Tom’s death, Brown invited Keats to live with him at Wentworth House, an offer Keats gladly accepted. Except for the summer of 1819, when he went to the Isle of Wight, Keats lived and worked there, but the disease which killed his mother and brother had begun to take its toll on him as well.

Keats took laudanum, commonly prescribed by doctors at the time for pain (Keats himself, trained to be a doctor, would have been well aware of this). Opium was also commonly used. It wasn’t only poets and writers who used the drugs but we likely know more about their drug use than others’. Keats biographer Nicholas Roe points out that Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” and Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” are two of the “greatest re-creations of a drug-inspired dream-vision in English literature.”

In January of 1821, Keats’ condition was so bad that friends finally convinced him to move south to Italy, in a last desperate bid to save his life. Painter Joseph Severn traveled with him and stayed with him, nursing him through his illness to the end. He died on Feb. 23, 1821, and was buried in Rome, in the Protestant Cemetery. At his request, his gravestone did not include his name. Friends added some words, but Keats wanted this as the engraving: “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” When Severn died in 1879, he was buried next to Keats.

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. To hear those words on this Heath, on a day alternating between sunny and cloudy, is to hear the poet calling across almost 200 years.

Anita finishes this discussion by reading this poem by Keats.

Bright Star

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

During November, I’ve been posting a series on the poet John Keats. Next week, we’ll finish up with looking at Keats at Wentworth House, where he wrote some of his finest poetry.

Photo by Andy B, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

Megan Willome says

Thanks for helping me with Keats, Glynn.