It’s September, 2012. We’re on vacation in London, and I’m on my second visit to the Tate Modern. My first visit, two days earlier, was simply to see the collection and the museum’s incredible interior space (the Tate Modern occupies what was formerly a large power plant on the Thames River). This second visit is to see the current exhibition – Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye.

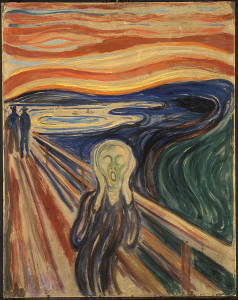

The exhibition does not include the only Munch painting with which I’m familiar – The Scream. The reason is that the exhibition covers only Munch’s 20th century works (including experimental photographs). The Scream, all five or so versions of it that he painted, dates from about 1895.

That’s something I learn from the exhibition. Munch (1867-1944) returned to the same themes over and over again, and not only with The Scream. The Sick Child (likely based on the experience of his sister) and The Girls on the Bridge are two other subjects that he returned to again and again. He also painted women, in all stages of dress and undress. And mundane events like men walking to work and more sensational events like house fires also inspired his painting.

That’s something I learn from the exhibition. Munch (1867-1944) returned to the same themes over and over again, and not only with The Scream. The Sick Child (likely based on the experience of his sister) and The Girls on the Bridge are two other subjects that he returned to again and again. He also painted women, in all stages of dress and undress. And mundane events like men walking to work and more sensational events like house fires also inspired his painting.

Two years later, on another London vacation and browsing the Tate Modern’s shop, I find The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth, edited and translated by J. Gill Holland.

Edvard Munch wasn’t only an artist. He was also a poet. Poetry is the primary form he used for notes observations, reflections and ideas he wrote in his private journals. He wrote about the women he painted, and women in general (long poems about women; really long poems). He wrote about fellow painters. And he wrote about his own paintings. This is what he wrote about The Scream:

One evening I was walking

out on a hilly path

near Kristiania—

with two comrades. It

was a time when life

had ripped my

soul open.

dipped in flames

below the horizon.

It was like

a flaming sword

of blood slicing through

the concave of heaven.

The sky was like

blood—sliced with

strips of fire

—the hills turned

deep blue

the fjord—cut in

cold blue, yellow, and

red colors—

The exploding

bloody red—on

the path and hand railing

—my friends turned

glaring yellow white—

—I felt

a great scream

—and I heard, yes, a great

scream—

the colors in

nature—broke

the lines of nature

—the lines and colors

vibrated with motion

—these oscillations of life

brought not only

my eye into oscillations,

it brought also my

ear into oscillations—

so I actually heard

a scream—

I painted

the picture Scream then.

Not all of the poems are so detailed about his paintings and yet, collectively, they are all about his art and his work (the journals also include a number of pen-and-ink drawings and his observations about them). But we are dealing with art here, and art may be true without being factually true. And so it is with Munch’s writings in his journals; he himself warned that the journals were both fact and fabrication.

But the poems also stand on their own. As Holland, professor emeritus of English at Davidson College in North Carolina says in his introduction, “It is not necessary to read Munch’s journal entries simply as a verbal reflection of his visual art. These stories and meditations stand on their own in the European literary world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

Thinking back to the Tate Modern exhibition, I can recall being overwhelmed by the breadth of the works assembled for the exhibition. Munch would have been pleased, I think. As he writes in one of his journal entries:

It suits

my pictures to hang together; they

lose something displayed with

others.

Photo by fOtOmoth, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

Interesting post, Glynn. I appreciate the ambiguity in Munch’s writings, how we might not be able to discern fact from truth from lie.

Glynn says

After reading his journal entries and seeing that exhibition, I wonder if he knew the difference all the time.

Marcy Terwilliger says

Glynn, you are a traveling man and I wish I had been the fly on the wall. Having studied Munch in Art School it was all about the “Scream.” I don’t recall anyone bringing up the fact he was a poet. His art//paintings were not the norm so he stood alone in his work, yet his colors drew you in and that face of horror. Thank you for presenting another side of this artist, one would have never dreamed he wrote poems also.

Glynn says

Marcy, thanks for reading and the comment.

Bethany Rohde says

Thank you for sharing about Munch’s poetry. It’s fascinating to see the painting side by side with his poem about it. I was intrigued by the journal entry you close the post with. Thanks again.

Dolly@Soulstops says

Glynn,

So interesting…it made me wish I could paint because sometimes words are inadequate for one is feeling…Thanks for enlightening me…again 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

I took one of those silly buzzfeed quizzes on art last week that involved matching artists with paintings. I guessed almost all–except like Mona Lisa and The Last Supper–and I scored very high. What a hoot. I must absorb some of what I read here without knowing it. But I guessed right on The Scream before you wrote about it. 😀