Christine Rhein might be the poet of displacement. Or dispossession.

Christine Rhein and her sister were born in America and raised in the Detroit area. Christine herself made a home there, developing a career as a mechanical engineer in the automotive industry. Yet one of the formative influences of her life happened decades before and thousands of miles away.

Her father, Horst Misch, was born in Silesia in 1931. Originally part of Poland, the area had passed to the Hapsburg Empire in 1335 and then to Prussia in 1742. People of German heritage had lived there for seven centuries. To the south was the Sudeten Mountains, a region carved out of the Habsburg empire after World War I and incorporated into the new country of Czechoslovakia.

In 1938, the troops of Nazi Germany occupied the Sudetenland, incorporating the German-speaking area into Germany and establishing a puppet regime in Prague. The next year, with the invasion of Poland and the start of World War II, Germany annexed Silesia as well. Silesian Poles were deported, and German settlers moved in alongside the already substantial German population living there. At the end of the war, the region was overrun by Russian troops.

Christine’s father was now 14. His own father, enrolled in the army, disappeared in the destruction of German armies. The young teen and his mother were expelled from their home, fleeing first to Czechoslovakia and then to Poland. Eventually, the young man made his way to America, as did the woman he married, a Polish German with a similar story.

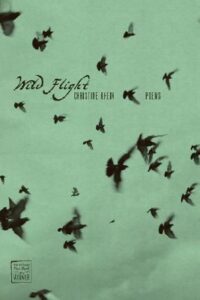

Rhein tells their story in part I of Wild Flight: Poems. It’s the story of Horst and his wife, Eleonore, a story of displacement and dispossession, a tearing away of the familiar and being pushed and shoved into the unfamiliar. For all of the upheaval they experienced, they were among the fortunate ones; some two million Germans died in the postwar chaos, forced evictions, and resettlement elsewhere.

That experience of war, destruction, flight, displacement and resettlement shaped the rest of her father’s life, and thus Christine Rhein’s own as well. As in any family, there would be stories, stories that would explain how a Silesian German born in Poland would come to live in Detroit, Michigan. And the stories might fade over time, but they would never go away entirely.

from My Father’s Geschichte (story or history)

He says the nightmares stopped sometime

He says the nightmares stopped sometime

in his forties, the ones I witnessed in childhood

when he napped on the couch, shouting

himself awake—January 1945 all over again,

the run from Russian troops moving west,

burning homes, raping women—and always

the same dream: his mother hidden while he

stood lookout, his body pressed against the door,

soldiers laughing, pushing from the other side.

At seventy, he nearly chuckles at the long-lived fear,

the way he does when his accent prompts

someone to ask where in Germany he’s from

and he begins, I’m not sure how much you know

about history. Have you heard of the Oder River?

Well, I was born on the wrong side of it…

The poem continues with the family’s wintertime escape, people fleeing with a few possessions in suitcases or wooden carts, “just a day ahead oof the Russians.”

Christine Rhein

The collection has five parts; the story of her father is largely in the first part. But those poems are the formative ones for those that follow – Christine’s own life, her experiences with her sons, her meditations on art, family life, washing windows (and remembering the German poems her father taught her), and even a story about chimney swifts, which at least possess the good fortune of having claws to cling to the sides of walls and cliffs.

Rhein’s poems have been published in several literary journals and magazines, including The Gettysburg Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Rattle, and Southern Review, among many others, and they’ve been included in anthologies like Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, Best New Poets, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. Wild Flight won the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry. She lives in Michigan.

Wild Flight is poetry, history, contemporary life, and family, all told in a narrative and understated style. Rarely have I felt so moved by a collection’s substance, but this one did that and more.

Related:

When You Don’t Speak Czech or German.

Photo by Martin Fisch, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

![]()

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Christine Rhein and “Wild Flight” - October 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Peter Murphy and “You Too Were Once on Fire” - October 14, 2025

- “Your Accent! You Can’t Be from New Orleans!” - October 9, 2025

Leave a Reply