Beth Copeland turns to the mountains to find healing

When I was a child, my parents had a favorite vacation place—the mountains. When you’re a flatlander or an “indented” flatlander in a subsidence-prone city like New Orleans, the mountains seem almost like a catapult to the heavens. The focus was the Smoky Mountains and the Blue Ridge Mountains.

We stayed in places like Gatlinburg, Tennessee, before it was discovered; Luray, Virginia, with its caverns; and Cherokee, North Carolina. One of my most vivid memories is the family hiking up a mountain in Virginia to an overlook point, with the Shenandoah Valley laid out below.

The mountains, those unmovable heights of rock, dirt, and trees, brought awe, wonder, and a sense of peace. Occasionally, the snaky roads through them brought bears and cubs. (Everyone pulled over the see the cubs; few stopped for the full-grown bears.)

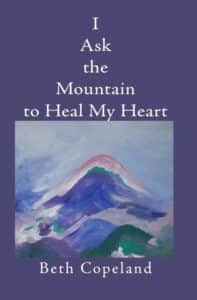

For poet Beth Copeland, the mountains brought peace and something else—healing. A relationship had ended, and she moved to the mountains for solace. It was perhaps inevitable that she would write about it, and I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart: Poems is the result. And what a beautiful result it is. When I began reading, I didn’t expect to find some of my own story, but that’s what happened.

Copeland sees the mountain near her home as something permanent, “a point of reference / to keep us from becoming lost.” And it does this by “being a steeple pointing to the sun, moon, and stars / to remind us: We are not lost. We are exactly where we are.” It was the sense of permanence, of something larger and more lasting than we are, that my own mother would mean when she said the mountains made her feel closer to God.

The poet meets people in her mountain home—an evangelist, a hunter, a saleswoman who’s actually looking for something to eat. She is reminded of the failed relationship—a phone call, a memory, a physical feeling. She begins to understand the things she still loves and the things she didn’t know she loved.

And she beings to find herself. She’s reminded of her family ancestry, and the long line of lumberjacks she’s descended from. “Sawdust is in my blood,” she writes. And she begins to see that what we love most, what we most find comfort in, can also consume us.

Lost Cove Wildfire

a fire spreads on Christmas Eve, then smolders

under snow, but snags and smoke remain

as firefighters in California find ghost trees

on the forest floor, scorched imprints

of fallen trunks, branches, and twigs.

Meanwhile, my sister builds a fire in her house,

tosses kindling on logs and, in lieu of a bellows,

blows on the blue blaze to keep it burning.

How thin is the wire between the flaring flame

in the hearth —the heat, the heart!—and the wildfire

that starts with a single spark?

As she rediscovers solace and solitude, she begins to understand just how much of the mountain is in her blood, the shelter it provides, and while it is a stationary, permanent thing, its face changes with the time of day and with the season. Mountains and the landscapes around them have their own rhythm, their own moods; she even includes a poem describing the mountain as her mood ring.

Beth Copeland

Copeland previously published five poetry collections: Traveling through Glass (1999), Transcendental Telemarketer (2012), Blue Honey (2017), Selfie with Cherry (2022), and Shibori Blue: Thirty-six Views of The Peak (2024). Her poems has been published in numerous literary journals such as Hunger Mountain, The Ledge, Rhino, and The Emily Dickinson Anthology and received a wide array of poetry awards. She lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The title I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart begs the question: did the mountain grant her request? The answer is likely yes. “When the mountain sleeps,” she writes, “I Sleep. When I wake, / I greet its granite face with love and gratitude.”

And I’m reminded of the gratitude I felt when I waded among the rocks of the Little Pigeon River in Tennessee, and how I was safely asleep that night in a hammock on a screened porch, hearing the thunderstorm and the roaring the river below. And I’m grateful for this poetry collection; I read Copeland’s 52 poems and walked into my own memory, and my own life.

Photo by Pacheco, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Catherine Strisik and “Goat, Goddess, Moon” - September 25, 2025

Bethany R. says

Love those lines from Beth Copeland – “a steeple pointing to the sun, moon, and stars / to remind us: We are not lost. . .”

Your closing memory of being “safely asleep that night in a hammock on a screened porch, hearing the thunderstorm and the roaring the river below” is such a comforting one. Thank you for sharing this with us, Glynn.

Glynn says

Thanks for the comment, Bethany.

Bethany says

And your image reminded me of a painting I recently saw online, “Distant Thunder,” by Andrew Wyeth. It’s not exactly what you describe, but it feels to me like a restful comfort of a scene, though storms rumble in the distance.

Glynn says

I had to look it up – Wyeth is a favorite artist. It is the general idea (without the dog – we had to leave outs at home.)