Poet Maurice Manning has done something unusual for a poetry collection. He’s crawled inside the head of a famous historical figure and told stories about the man’s life from his own posthumous perspective.

In Railsplitter: Poems, the historical figure is Abraham Lincoln. Manning explains that his affinities for Lincoln have been long-standing. “I grew up near his birthplace,” he writes in the preface, “and I live in the same county where his parents were married. My ancestors were early settlers of Kentucky. All my life I have had a sense of the world Lincoln came from, and meeting him through poetry has seemed, especially in recent years, inevitable.” He says his great-great-grandfather would boast that he voted for Lincoln twice.

It was Lincoln who drew me to Manning’s collection. I came late to Lincoln, growing up in the South, with a family invested in the Civil War and its memory and re-invention. Lincoln was rarely spoken of, and when he was, it was not with admiration. When I was an adult, and working as a speechwriter, I discovered Lincoln first through his speeches, like the Second Inaugural Address and especially the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Once I discovered him, Lincoln became almost heroic, because he was, a plain-speaking frontier lawyer who led the United States through the most difficult period of its history.

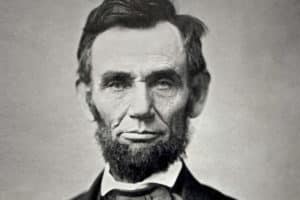

Abraham Lincoln

In Manning’s poems, you find a Lincoln who sounds so authentic and realistic that you think the man himself must have written these first-person poems. It’s that realistic and compelling. In no chronological order, the poems consider scenes of boyhood, his years as a frontier lawyer, his own family, the Civil War period, and even his assassination at Ford’s Theatre in April 1865. Avoiding chronological order is important. Manning’s Lincoln understands and remembers his own life like we all do—with the stories we and others tell about ourselves; we don’t tell them in the order that they happened.

The collection begins with the surprising “To a Chigger,” the mite long famous for aggravating and irritating people in woods, grasses, beds, and anywhere else people inhabit. Growing up on a farm and sleeping in hotel beds when he argued various legal cases, Lincoln would have been more than familiar with this pest. But then the collection moves on to consider language, the Wilmot Proviso, rumors about rearing his children, the Know-Nothings, Transcendentalism, his law partner William Herndon, the Civil War, his assassination, the poems he wrote (including the vulgar ones), the Civil War, reading Robert Burns, and more.

The collection contains many poems that are moving, and they tend to be the ones that capture his struggles as a leader and the great loneliness he must have felt.

The Winter of My Discontent

and February was the depth,

and yet the grief went deeper still,

continuing as an endless valley,

and I was walking down it alone.

Death was everywhere a fog

over the land, and in my house,

I concluded, was where the fog began,

I was alone, as I am now,

to pronounce my soliloquies in the dark,

and my thoughts did dive down.

Am I a living ghost? What fate

is now foreshadowed by this moment?

How desperate must I be in this scene?

What resolution must I make?

To call for a horse? Where would I go?

Something happens to time in despair.

It ceases to divide, and yet

division was my residence.

So practicing soliloquies

revealed my mind, and the absence of time

gave me, strangely, time to practice.

And I had a discerning audience,

one who was familiar with my voice.

Maurice Manning

The title poem, “Railsplitter,” is the final poem, a meditation upon Lincoln’s death, his legacy, and the meaning of one’s life. Rarely have I been so moved by a poem.

Manning has published six other poetry collections, including Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions (2001), A Companion for Owls (2004), Bucolics (2007), The Common Man (2010), The Gone and the Going Away (2013), and One Man’s Dark (2017). A native of Kentucky, he attended Earlham College and the University of Alabama. After teaching at both DePauw and Indiana universities, he joined the faculty of Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. His poems have appeared in numerous literary publications. He was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry in 2011 for The Common Man and was named a Guggenheim Fellow that same year.

Railsplitter is a collection for our divisive time. Like Lincoln, we live in a sharply divided country, and we’re not even sure if we want to continue living together. Lincoln, and Manning’s poems about him, remind us that the difficulties may seem insurmountable but that there is always hope, and we were born for such a time as this.

Photo by Johan Neven, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and the newly published Dancing Prophet, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

- What Happened to the Fireside Poets? - June 24, 2025

Maureen says

I will have to read this collection (Lincoln is one of my heroes).

You would appreciate Gray Jacobik’s ‘Eleanor: Poems’ from CavanKerry Press. A week or so ago, I heard Jacobik read from the collection. She was marvelous, and her monologues in Roosevelt’s voice are wonderful.

Glynn says

Maureen, thanks for the reference. I will check it out.

Sandra Heska King says

This sounds wonderful. My husband loves Lincoln. This could even get him to like a little poetry.

Bethany R. says

That’s a cool idea, Sandra. Makes me wonder, what first drew you (and anyone else reading this) into poetry? Or have you always loved it?