It was 1843. Charles Dickens was publishing Martin Chuzzlewit in serial form, and the story wasn’t doing that well, at least compared to his earlier books like Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby. And Americans hated it; Dickens came close to losing his American audience for his portrayal of Americans he drew from his recent visit. His household expenses were rising, particularly with a new baby coming, and he had just learned that his usually spendthrift and almost always broke father was expecting him to pay his debts.

He needed something, something new, something to recapture the public’s imagination.

In October, Dickens traveled to Manchester, to give a speech and to visit his beloved sister Fanny and her family. He was especially concerned about his young nephew Harry, who’d been born with a number of serious disabilities; his parents didn’t expect him to live to adulthood. Before the speech, as he walked around the city, he was horrified by the plight of poor families and how they lived. It was as bad as it was in London. His speech at the Manchester Athenaeum Club was full of controlled outrage over the conditions of the poor and what Dickens saw as the evidence of lack of learning and education. Young children were working in factories. Families were living on the streets. The speech was reported all over Britain.

When we read the story, we focus on the miser Ebenezer Scrooge and his three Christmas ghosts (actually, there are four, counting Scrooge’s deceased partner, Jacob Marley). We chuckle knowingly at the antics and language of the stingy Scrooge, with his suggestions to “lower the surplus population.” Our hearts go out to Tiny Tim and the Cratchit family, whom Dickens depicts with great nobility of spirit in spite of their dire financial circumstances. Often overlooked are the two characters who are perhaps the point of what Dickens was trying to achieve: awareness of the two children enfolded within the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present, named Ignorance and Want.

Yes, it was a sentimental book, appealing to our emotions. But it worked. It still works.

It was one of those moments when all of the cultural planets seemed to align. People were experiencing a strong sense of nostalgia about Christmas, thinking that something of the old-time celebration and observance had been lost. Older people remembered what Christmas had been like in their youths, when high- and low-born celebrated together, with festive gatherings and parties. The Industrial Revolution was in flood tide, and Christmas seemed to be getting crushed. Millions were less concerned about celebrating the spirit of the season than they were about where their next meal was coming from.

That was the context into which A Christmas Carol arrived. Coincidentally, Christmas of 1843 also saw the appearance of what would become a staple of the season—the very first Christmas card. And a few years later, when a magazine published a story depicting how the British royal family celebrated Christmas (Prince Albert, Queeen Victoria’s German husband, brought with him the German tradition of decorating cut trees indoors), still another tradition was born.

Dickens, however, is the writer we most closely associate with Christmas, and not only because of A Christmas Carol. He wrote a total of five Christmas books, all of which were eagerly bought by the reading public but none of which achieved the acclaim of Carol. And his novels and magazine articles contain repeated references to Christmas.

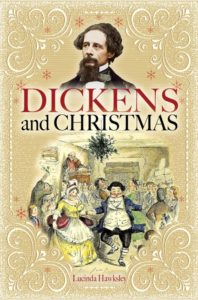

Lucinda Hawksley

Lucinda Hawksley, a great-great-great granddaughter of Dickens, has collected all the author’s connections to and inventions of Christmas in Dickens and Christmas. She covers in detail the background of Dickens’ understanding of and experience with Christmas, and then proceeds to tell a kind of “Christmas biography” of the author.

She describes his own childhood, what Christmas was like in the 1810s to 1830s, and the role of pantomimes and theater in celebrating the season (Dickens wanted to be an actor long before he began writing his stories, and theater remained a significant part of his life.) Then she tackles how Dickens depicted Christmas in his books and how the five Christmas stories came to be.

Her book is relatively short for the subject—some 200 pages, including an index. But it’s packed with information about how Dickens transformed Christmas, and how it came to be the season we recognize today, for better or worse.

Hawksley has published Charles Dickens and His Circle; The Mystery of Princess Louise: Queen Victoria’s Rebellious Daughter; Essential Pre-Raphaelites; Charles Dickens’ Favorite Daughter: The Life, Loves, and Art of Katey Dickens Perugini; March, Women, March; and several other works. She’s also an art historian and public speaker, especially on environmental causes.

A Christmas Carol helped transform Christmas into the celebration we know today. While we often rail against the commercialism of the season—for many retailers, Christmas now starts before Halloween—it is also a time we remember our own childhoods and our families, we are inspired to generosity and kindness, and we recall our own and others’ basic human needs to be loved and cared for. And we can thank Scrooge and Tiny Tim and Bob Cratchit and those ghosts for helping to translate the original Christmas story into a cultural Christmas story.

Photo by ABBones, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of Poetry at Work and the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and the newly published Dancing Prophet.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

Megan Willome says

I knew some of this background, but not that there was a speech!

I used “A Christmas Carol” in my most recent Tweetspeak workshop, and most of the participants had not read it, although everyone had seen multiple adaptations. But you’re absolutely right: “It still works.”

P.S. “A Muppet Christmas Carol” has my vote for the best ghosts.

Glynn says

My wife and I loved “A Muppet Christmas Carol.” My personal favorite is “Scrooge,” the musical from 1970 with Albert Finney as Scrooge, Alec Guinness as Jacob Marley and Dame Edith Evans as the Ghost of Christmas Past. It used to be shown on television quite a bit and we have the cassette tape version; just two weeks ago I bought the DVD version.

Michele Morin says

I’m so glad to read some back story to this great Christmas story. Our favorite movie adaptation is the one featuring George C. Scott as Scrooge. It’s become a family tradition to watch it on Thanksgiving night.

Glynn says

Michele, we like that version, too. We refer to as “Patton does Dickens.”