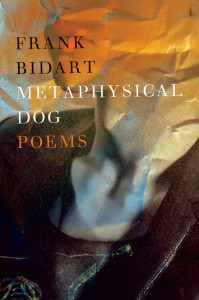

Reading Frank Bidart’s new collection of poems Metaphysical Dog, I learned something about how I read poetry. I learned from the absence of something.

In reading a poetry collection, I usually look for one poem, any poem, that will center the entire collection for me. It might be the title poem, though it often isn’t. But one poem becomes, for me, the filter for the rest, a kind of prism of understanding what the poet has done with the poems he or she has included in this particular collection. I admit that this may be a practice peculiar to me.

I didn’t find that one poem in reading Metaphysical Dog, even after reading it three times.

However, I had a fall-back position. I ended up reading the collection of 39 poems as a single poem, each individual part blending into what preceded and what came after. I don’t believe Bidart wrote the poems that way, but that is how I ultimately understood the collection.

Collectively, and even when I break them apart individually, these poems pack a powerful emotional wallop. You begin the reading the first poem, the title poem, and without realizing it you’re soon hurtling through a highly personal, highly emotional experience.

The poems range across the poet’s life, not in chronological order but in what might be called an increasing intensity of experience. Here’s “Like, ” which comes early on in the poems:

by like. Your hands were too full, then

empty. At the grave’s

lip, secretly you imagine then

refuse to imagine

a spectre

so like what you watched die, the unique

soul you loved endures a second death.

The dead hate like, bitter

when the living with too-small

grief replace them. You dread

loving again, exhausted by the hungers

ineradicable in his presence. You resist

strangers until a stranger makes the old hungers

brutally wake. We live by symbolic

substitution. At the grave’s lip, what is

but is not is what

returns you to what is not.

From there, Bidart doesn’t move forward or farther; he moves deeper, deeper into family, self, and gender confusion followed by acceptance (although acceptance arrives before confusion). He talks about, with, and to Walt Whitman, whom he could have been referring to in “Like.” He travels toward the absolute and then away from it.

He arrives, in “Of His Bones Are Coral Made, ” at transformation, and it is an arrival at the end of his life, not at the beginning:

He still trolled books, films, gossip, his own

past, searching not just for

ideas that dissect the mountain that

in his early old age he is almost convinced

cannot be dissected:

he searched for stories:

stories the pattern of whose

knot dimly traces the patterns of his own:

what is intolerable in

the world, which is to say

intolerable in himself, ingested, digested:

the stories that

haunt each of us, for each of us

rip open the mountain…

The four poems that follow are not so much post-climactic as they are a quiet acceptance and understanding.

Bidart has written numerous collections of poetry and received many awards, including the Wallace Stevens Award and the Bollingen Prize. He is a “presence” in contemporary American poetry, but more than that, he continues to create collections like Metaphysical Dog that perplex, amaze, provoke, and then, oddly, bring calm and understanding.

Image by articotrpopical. Sourced via Flickr. post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining.

Browse more Poetry at Work

___________________________

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.

We’ll make your Saturdays happy with a regular delivery of the best in poetry and poetic things.

Need a little convincing? Enjoy a free sample.

- Poets and Poems: Beth Copeland and “I Ask the Mountain to Heal My Heart” - July 10, 2025

- A.E. Stallings: the Parthenon Marbles, Poets, and Artists - July 8, 2025

- Poets and Fables: Steven Flint and “The Sun and the Boy” - July 3, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

Thoughtful look at Bidart, Glynn. I’m struck by the starkness, and the repetition that seems to betray some kind of deep seeking that isn’t resolved through memory and maybe not even through art.

Glynn says

Maureen – I think he uses repetition in exactly that way. These were deep poems to read and consider. And very personal – but that’s one of his trademarks.