Alfred Nicol plumbs the depths of human existence

When you’re born and raised in New Orleans, you soon learn that one holiday frames and defines the city. The Mardi Gras season stretches for some three weeks before the final day of Shrove Tuesday. It’s filled with parades of floats with their masked revelers tossing beads and other trinkets to the crowds, marching bands, costumed balls, and (at night) the flambeaux carriers walking with the parades.

My mother, also a native New Orleanian, always referred to Mardi Gras as “Carnival,” like its Brazilian counterpart.

Mardi Gras culminated on the Tuesday before Lent, with what seemed a series of endless parades beginning with the Krewe of Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. It was followed by the parade of the Krewe of Rex, King of Carnival, and the “truck” parades of Crescent City and Elks, ending with the nighttime parade of the Krewe of Comus (now discontinued). The balls of Rex and Comus were held at Municipal Auditorium, and at midnight, the two courts would meet and officially end the Mardi Gras season.

Alfred Nicol

After carnival came Lent. Tuesday was excess in all of its varied forms; Wednesday was restraint and ashes on the forehead. Experiencing Mardi Gras in New Orleans was like experiencing a cultural theology, moving from riotous sin to humble repentance.

Reading After the Carnival: Poems by Alfred Nicol is a Mardi Gras kind of experience, plumbing both the depths and the heights of human existence. Unlike Mardi Gras, the collection doesn’t have a changeover at midnight. Instead, the depths and heights are mixed together, occupying adjacent spaces and sometimes the same space.

The man in the middle must be a traitor to our side; he’s torn apart (by both sides) and discarded. In “The Ballad of the Terrible Silence,” a child is smothered in seat cushions. A storyteller descends into madness. “Stay at Home Advisory” suggests that a pandemic warning is that different from normal life, where the unhealthy and the isolated continue to be shunned.

Yes, life is full of evil. And yet Micol writes of poets (“Poemmakers”), even if they might be considered hobbyists instead of having a real job. And birds, as in “Altogether Alive,” which have their own stories and ways of conversations. And he suggests how to make war, which might be more positive than it first sounds. Maybe. Or perhaps it’s simply ambiguous, like much of life, and like many of these poems.

An Indelicate Proposal

and shake them from the napping-dream of peace;

let them rejoin the wars that never cease

and heat thin blood to simmering again.

When young men die in battle, more is lost.

By laying down their lives when they are strong

for fields they haven’t harvested as long,

they pay a lesser debt at greater cost.

So let us press the elders into service.

They will be recognized and celebrated,

no longer penned inside, emasculated,

clucking like old hens, ruffled and nervous,

ready for the freezer or the fryer.

What difference if the end is ice or fire?

Nicol has previously published several poetry collections, including Winter Light (which received the Richard Wilbur Award), Elegy for Everyone, Animal Psalms, and collaborations with poet Rhina Espaillat and his sister, artist Elise Nicol. He’s also translated One Hundred Visions of War by Julien Vocance. His poems have appeared in Poetry, The New England Review, Dark Horse, Commonweal, The Hopkins Review, and other literary publications. He lives in Massachusetts.

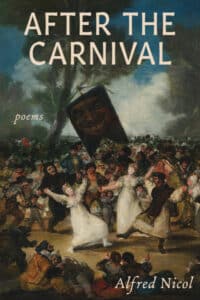

The cover illustration for After the Carnival is The Burial of the Sardine, a late painting by Francisco Goya (1746-1828). It depicts the ending procession during the three-day carnival in Madrid roughly equivalent to Mardi Gras. A mostly masked crowd is dancing while escorting a banner of the king of carnival. Three figures stand out – two dancing women dressed in white, followed by a dancing figure dressed as death. It’s a rather creepy painting, not unusual for Goya’s late works. Like the fine if unsettling poems inside After the Carnival, the festivities are ending; repentance and judgment lie directly ahead.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Julien Vocance and One Hundred Visions of War

Photo by Vinoth Chandar, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Donna Vorreyer and “Unrivered” - October 7, 2025

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

Leave a Reply