Kelly Belmonte sits in the quiet of a loved life

As I began reading The Mother of All Words, the new poetry collection by Kelly Belmonte, an image of my childhood began to emerge: the neighborhood where I grew up in suburban New Orleans. It has originally been something akin to swamp; our corner house’s lot still had two swamp cypress trees. And across the street were the woods stretching several blocks. As kids, we called it the “Little Woods,” to differentiate it from the wooded area on the other side of the drainage canal. That was the “Big Woods,” four to five times larger, which had what seemed like acres of blackberry bushes scattered among the trees and brush.

Living near woods as a child was sheer magic. My childhood wasn’t especially notable or exceptional, but we had the woods, with its trails, its hiding places, its space so deep you could lose sight of the nearby houses. You could imagine anything and imagine yourself to be anything. And adults were nowhere to be found.

Early on in Belmonte’s collection, I read this poem, which was almost a generation later from my own but captured that childhood experience almost exactly.

Latchkey Kids

It was years before I realized they meant

us. We were pre-teens with keys,

unlocking doors, preparing supper,

riding bicycles without helmets—

without a thought for safety.

We roughed our way across the creek,

through the woods, never worried

about ticks. We climbed to the top

of the old oak and ripped our pants

on the way down. Played

hide & seek until sunset, or until

someone’s mom yelled “Dinner!”

We stumbled back through the front door

trailing the scent of sweat and freedom.

Maybe we washed up, did some homework,

maybe we watched TV. Whatever we did

after we let ourselves in, we felt

safe as houses.

The difference for me was that we didn’t have keys; our mothers were all at home. Even without the keys, we felt “safe as houses.”

The sense of living a loved life pervades The Mother of All Words. The collection doesn’t suggest smugness or even satisfaction, but more of a sense of gratitude. I can imagine Belmonte writing these poems as she looks out toward woods; it might even be those childhood woods I went romping through.

She divides the work into three parts.

The first is “Place in Time,” which reflects the small things we take for granted in our lives — measuring time, a tin full of buttons, the hard work of picking beans, taking out the trash, zucchini growing the garden.

The second section is “Word Barn,” which is mostly about poetry, like how to write a poem (it has something to do with tea), the value of a poem, how all poetry is “found,” and why it’s not a hobby. The title poem is included in this section, and I won’t say what the mother of all words is (but I guessed it by the time I reached the poem).

The third section is “Presence and Prayer.” These poems include living in the time you’re born, walking without shoes, and prayers for both an offended world and the disillusioned idealist.

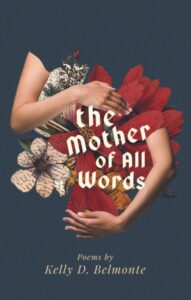

Kelly Belmonte

Each section contains some lovely poems, poems you will want to sit with and read and speak aloud. The poems are quiet and thoughtful as she considers each subject and each theme.

Belmonte previously published three chapbooks, Three Ways of Searching (2013), Spare Bottoms (2014), and Transit (2022), a poetic and photographic collaboration with Tom Darin Liskey. (Disclosure: I wrote the introduction for Transit.) She received a B.A. degree in English Literature from Gordon College, and her work has been published in a number of literary magazines and journals. Her work has also been included in poet Malcolm Guite’s anthology Word in the Wilderness (2104) and in the Women and C.S. Lewis anthology (2015). She lives with her family in Maine.

My “Little Woods” and “Big Woods” disappeared decades ago, replaced by suburban housing tracts. But I can read The Mother of All Words and remember the blackberry bushes, the endless games with neighborhood kids, and the magic of a childhood.

Related:

Poems and Photos: Kelly Belmonte, Tom Dair Liskey, and Transit

Photo by Franklin Hunting, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- “The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain” by Kazuo Ishiguro - November 13, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Steven Flint Embraces Haikus - November 11, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Quiet Woman” - November 6, 2025

Bethany R. says

Love how Kelly starts that poem,

“It was years before I realized they meant

us.”

Hooks me right in, and I get it. Thanks for this review of this collection! I bought it as well and have read many of this poet’s pieces over the years. What a delight.

Glynn says

I really like Kelly’s poetry. Thanks for reading and the comment!