After occupying the literary heights in 19th century America and beyond, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) became the figurative statue to topple for literary critics in the early and mid-twentieth century. And topple him they did, with a bevy of prominent literary critics dismissing the poet as unworthy of the literary canon. Proponents of the “isms” — like Modernism and the New Criticism — banished Longfellow from any serious consideration.

Yet millions of Americans loved this poet, whose works became bestsellers in the United States, who outsold Robert Browning and Alfred Tennyson in England, who was translated into dozens of languages in his lifetime, and who occupied the pinnacle of the American literary establishment for several decades.

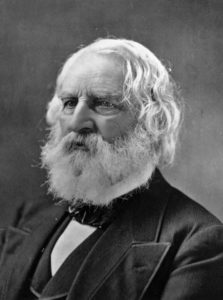

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Frances Appleton Longfellow

Sentiment changed, beginning in the late 1950s, says biographer and author Nicholas Basbanes in Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In 1959, Howard Nemerov edited a volume of Longfellow’s poetry. Other poets and writers began to write appreciative books and essays. His rehabilitation was assured with an essay in 1993 by poet Dana Gioia. A long and overdue examination of Longfellow’s poetry was well underway. So, too, was the contribution made by his second wife, Frances (“Fanny”) Appleton Longfellow (1819-1861). And it is understanding and chronicling that relationship and dynamic that Basbanes undertakes in Cross of Snow.

Fanny is most famous for being Longfellow’s wife (his first wife died from complications after a stillbirth) and for her tragic death in 1861, after a candle caught her dress on fire. Longfellow desperately tried to extinguish the fire, burning his own hands in the process. He was heartbroken for the remaining 21 years of his life. Basbanes argues, however, that she should be recognized and remembered for her first-rate literary mind and how she contributed to Longfellow’s work.

He examines her own letters and journals as well as contemporary accounts to suggest that Fanny Longfellow exerted significant influence on her husband’s literary output. The title of the book, in fact, is taken from the title of a poem Longfellow wrote for his wife in 1879, 18 years after her death.

Cross of Snow

A gentle face — the face of one long dead —

Looks at me from the wall, where round its head

The night-lamp casts a halo of pale light.

Here in this room she died; and soul more white

Never through martyrdom of fire was led

To its repose; nor can in books be read

The legend of a life more benedight.

There is a mountain in the distant West

That, sun-defying, in its deep ravines

Displays a cross of snow upon its side.

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

(“Benedight” is an obsolete word meaning “blessed.”)

This is the kind of book that comes along all too rarely. I was barely halfway through the introduction when I realized what a pleasurable experience it is to read a book like this. Basbanes’ admiration for Longfellow and his poetry is equaled by his admiration for Fanny. His goal is not to tear down, or even to build up, but to explore, explain, and reach a new, deeper level of understanding.

Nicholas Basbanes

The research behind the book is enormous, but the research informs the narrative; it doesn’t dominate it. The author explores the importance of several trips to Europe for both Longfellows (they actually met in Switzerland, even though they lived within a few miles of each other in the Boston/Cambridge area). And friends and acquaintances move across the book’s pages, including Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Julia Ward Howe, William Cullen Bryant, and many more.

Basbanes is also the author of On Paper, Patience & Fortitude, A Gentle Madness, and several other works of cultural and literary history. An award-winning investigative journalist, he was the literary editor of the Worcester Sunday Telegram and received two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities. He lives in Massachusetts.

I suspect Longfellow would be pleased with Cross of Snow, which both recognizes his own achievements and first-rate mind and also gives Fanny her proper due for her accomplishments and first-rate mind. It’s a literary biography of a couple who still help to shape American letters and literature.

Related: “A Beautiful Ending: On death and heaven in the time of Longfellow” by Nicholas Basbanes.

Photo by Ben124, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Alison Blevins and “Where Will We Live if the House Burns Down?” - July 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

- What Happened to the Fireside Poets? - June 24, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

It was a poem by Longfellow that reopened something between my mother and I.

How it happened:

I was interviewed by Basecamp’s Wailin Wong. During the interview she happened to ask me why my mother read poetry to us daily (I’d told her how my mom read to us every day). I realized I had no idea.

So the next time I talked to my mom, I asked her why. And her answer surprised me: “Because I loved poetry and I wanted you to love it too.” I assumed she’d read it to us to settle us before the school bus came.

Anyway, then I learned that she came to love poetry through Longfellow’s Hiawatha. And I bought her a book with that and more poems in it. She was thrilled. She even texted Sara afterwards and talked to *her* about Evangeline. 🙂

Glynn says

Growing up in New Orleans, as a child I thought “Evangeline” was a true story. It was, after all, family history (my maternal grandfather was Cajun/Acadian). Even after I realized it wasn’t a true story, it still was a “true story.”

When you consider it, Longfellow did some rather radical repositioning of some American myths. “The Song of Hiawatha” portrays native Americans in an extremely favorable light but was written at a time when they were still considered and called “savages.” And he wrote poems about slavery that were not well received in the slave-owning states.