The audience at the British Library for a discussion about a new annotated edition of T.S. Eliot’s poetry was largely academic: professors, students, researchers with the British Library, likely a few poets. And two Americans on (mostly) vacation. Our trip was punctuated by poetry and writing highlights: a Keats Walk in Hampstead and Hampstead Heath, a visit to the Charles Dickens Museum, the Samuel Johnson House, a visit to Merton College at Oxford (Eliot’s college and where J.R.R. Tolkien taught).

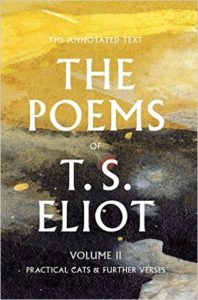

And finally, with two days left in London before we would depart, we were listening to this discussion at the British Library by Jim McCue and Christopher Ricks, co-editors of T.S. Eliot: The Poems, Vol. I (Collected & Uncollected Poems) and T.S. Eliot: The Poems, Vol. II (Practical Cats & Further Verses).

And the variations, said Ricks, often had to do with events in Eliot’s life. With Mr. Apollinax, for example, published in Prufrock and Other Observations in 1920, the versions changed to reflect what happened with submarine warfare in World War I. McCue adds an example: the prose poem The Engine, written in 1915 and previously uncollected, reflects Eliot’s experience traveling from England to the United States in 1915. “You cannot be on a ship going to the United States in 1915, ” McCue says, “and not think about the ship going down.”

And the availability of numerous manuscripts allowed the editors to trace the development of lines in Eliot’s poetry, like Four Quartets, over a period of years and in a variety of poems. But the process of sorting, analyzing and classifying those manuscripts and printed versions was intense.

McCue pointed out how much Eliot re-appropriated old ideas. “Eliot is very steeped in those old literatures he has read, ” he said, “and what a writer reads is often the most important part of what he does…A huge price is paid, and a huge reward received, for appropriating the old ideas and themes.”

The editors are asked if Eliot would have anticipated the annotation of what he produced.

“He would have been alarmed, ” McCue said, “but he would have wanted it. By the 1940s, he knows his place in literature. We know he didn’t want to be interpreted. This annotated edition won’t come between the poems and the readers; instead, editors should help readers and critics understand the poems.”

Ricks also responds to the question, but in a very different way, emphasizing the importance of reading Eliot for pleasure. “Unless there is a world that reads Eliot for pleasure, the world of the study of Eliot will cease to exist. The question we asked ourselves again and again through this process was how will people—the reader for pleasure—be helped by annotation?”

The discussion ends with a final observation by McCue, a recognition of the importance of poet Ezra Pound to T.S. Eliot’s poetry. “Eliot might have given up writing serious poetry without Ezra Pound, ” he says, “who saw Eliot as the greatest living American poet. Pound put up money he didn’t have to help publish Prufrock and Other Observations. He also pushed Eliot to write quatrain poetry, and he helped Eliot structure and restructure The Waste Land.

The discussion ends, but not the evening. The official publication date is Nov. 5, and at the time of the event, we are about three weeks shy of that. But copies are available, and without hesitation I buy both volumes (a not insignificant investment; at 40 British pounds each, the total comes to about US $130). And I will pack them in my carry-on bag for the flight home.

The books are a reminder of an evening discussion at the British Library about the man who was the 20th century’s greatest poet. They are also a reminder of a certain high school student, some 45 years ago, who read The Waste Land in his English class and was so taken that he bought Four Quartets during his next visit to the local bookstore, and who still has that treasured edition on his bookshelf. It is that same student who read Eliot for pleasure, and still reads Eliot for pleasure, and in so doing helps make the study of Eliot possible.

Related:

T.S. Eliot at the British Library, Part 1

Photo by Camilo Rueda Lopez, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Catherine Strisik and “Goat, Goddess, Moon” - September 25, 2025

Charity Singleton Craig says

Glynn – I find it very significant that even the scholars, the annotators, realize that if readers don’t approach poetry for pleasure that eventually it will lose its importance and its place in our culture. They understand that poetry is alive and needs to have a life of its own apart from the critics. I’m learning to engage poetry that way myself.

Your trip sounds amazing, every part of it. So glad you’ve been able to bring us along in the remembrance of it.

Glynn says

Charity, thanks for the comment. For whatever reason, the British seem to have a better understanding of poetry than their American counterparts. This particular comment was a welcome surprise.

Bethany says

Yes, I was delighted to hear the editor talk about the significance of reading Eliot for pleasure. Sometimes I get a bit intimidated by his writing and feel I need to understand every reference before I can just read through for the enjoyment of the words, cadence, and flavor of the piece. Maybe I should try it the other way around.

Glynn says

Bethany, way back in high school, I read “The Hollow Men” for an English class assignment. And then I discovered I could read it for pleasure (although a 16-year-old boy wouldn’t have described that way). I didn’t have any of the insight, academic credentials, or long years of study to be able to understand everything I was reading, but I could read it for simple enjoyment.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

Bethany says

Thanks for sharing that, Glynn. I haven’t read that particular poem yet. I’m going to give it a try now.

Megan Willome says

My thoughts exactly!

And just in case we are tempted to think no one cares about annotations, or that annotations are separate from enjoyment, those of us aboard the “Hamilton” speed train are eating up writer/composer Lin-Manuel Miranda’s annotations at genius.com. Enjoyment sometimes leads to geeking out.

Bethany says

Great point, Megan. For those who enjoy it, unearthing the sources and secrets of a text can be exhilerating.

L. L. Barkat says

Things especially of interest to me:

-the way Eliot changed the poems based on life. We tend to think of literature as static (and will even cry foul if a writer seems to be different from what he/she wrote long ago). Eliot seemed to refuse the static. Not that I recommend going back to change one’s work. I like to see my own as a record of development.

– “And his discernment of how much we feel in any given situation is stunning.” Yes and yes. Why do we expect ourselves and others to only feel one thing?

-All for the reading of anyone’s poetry for pleasure. And amused by something my daughter mentioned after part 1 of this post went live: She noted that Eliot was asked to explain his poems with footnotes and so forth by at least some of his publishers, and he made a lot of stuff up to do that, partly because he was asked and partly because he was a bit mischievous. “That’s why some of it makes no sense,” she said to me. “Because, it actually doesn’t. He made it up.”)

Bethany says

L.L., that is too funny about him making up footnotes!

Devon says

I hope to buy these annotated editions of Eliot’s work soon. As already mentioned, it’s neat how we can read poetry for pleasure and how great poems leave impressions on us even if we don’t understand every reference in the poems. Then we can return to a poem we love and see even more layers; I think annotations help us to see those layers. Thank you for sharing your trip experiences with us!

Bethany says

I agree, Devon. Fun to read your comment here. 🙂