Longfellow and the “Fireside Poets” deserve a better reputation

When I first envisioned my novel Brookhaven, I focused on a family story passed down through generations, which turned out to be a legend, as in almost entirely untrue. But two things shifted my focus.

First, in 2022, I had the old family Bible conserved. It had seen better days; my father gave it to me wrapped in grocery store bag paper and tied with string. My contribution had been to remove the paper and string, wrap it in acid-free paper, and store it in an acid-free box. It sat on a closet shelf for years, until I brought it to a book conservator in St. Louis. He discovered something tucked in the book of Isaiah that both my father and I had missed — a yellowed envelope containing a lock of auburn hair.

For various reasons, I believe the hair belonged to my great-grandmother Octavia. She died in 1888 at age 44. Unusual for the time, my great-grandfather Samuel never remarried. He died in 1920. And I thought to myself, “There’s a love story here.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Second, also in 2022, we saw a movie entitled “I Heard the Bells.” It’s a snapshot of the life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) during the Civil War, including both the tragic death of his beloved wife and the near death from a war wound of his oldest son Charles. Both events contributed to Longfellow’s writing the poem that became a Christmas hymn, “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.”

I was so taken with the movie that I started reading his poems, including some of the most famous ones of American history: “The Courtship of Miles Standish,” “Song of Hiawatha,” “Evangeline,” and “Tales of a Wayside Inn” (including “Paul Revere’s Ride”). Then I read all of his poems. I hadn’t read them since elementary school.

And my reading, and remembering many of these poems from my own childhood, made me wonder: what happened to Longfellow? Here was a poet who was one of the best-selling writers of the 19th century. His published works sold in the tens of thousands, often going through as many as six editions. He was popular in Europe as well; he was the first American to have a memorial bust placed in Poet’s Corner in London’s Westminster Abbey. But by the 20th century, while some of his poems might still be memorized by schoolchildren (like me), he’d been largely dismissed by critics as vastly overrated.

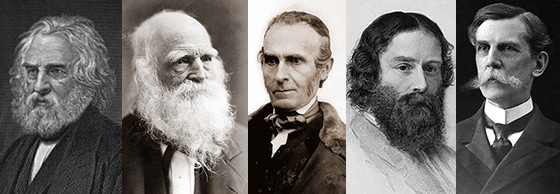

It wasn’t only Longfellow whose reputation suffered. The entire group of what was called “the Fireside Poets” and sometimes the “Schoolroom Poets” had been sniffed at and discarded like so many second- and third-rate writers. These included William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892), James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809-1894), in addition to Longfellow. But Longfellow had been the most popular and best loved.

I started reading and discovered at least two developments that could account for what happened.

Five of the Fireside Poets: Longfellow, Bryant, Whittier, Lowell, and Holmes.

First, critics embraced the Realists and then the Modernists, who had largely rejected the narrative poetry that had dominated since Homer. Narratives or stories were out; personal feelings were in. Some attribute the change to William Wordsworth in Britain and then Walt Whitman in America.

Second, with the decline in narrative poetry came a decline in the numbers of people reading poetry in general. Poetry was often published and avidly read in newspapers, but that had largely disappeared by the 1930s. Apparently, the reading public was far less interested in the poetry of personal feelings than in poems that told stories and could be easily memorized because of rhyme and meter. Poetry began its long march to academia, and there it remained until the age of the Internet.

The entire group of Fireside Poets deserves to be read. Several were Transcendentalists, part of an important literary and cultural movement. All were abolitionists, a few like James Russell Lowell ardently so. Their writings and poems helped propel the country toward what eventually became the Civil War.

Of the group, only Longfellow expressed regrets. After seeing the carnage that resulted in the deaths of 10 percent of the population, he regretted the role that he and his “Poems on Slavery” had played. He didn’t regret the end of slavey; he regretted the devastation that the end required.

Their poems are enjoyable to read, especially out loud. They’re meant to be recited, and they often were at family gatherings, on winter evenings after supper, and in schoolrooms. They helped shape the American character. And they still have much to say to us, more than 150 years later.

Related:

Longfellow and the Decline of American Poetry – The Scholar’s Stage

Photo by David Goehring, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Catherine Strisik and “Goat, Goddess, Moon” - September 25, 2025

Katie Spivey Brewster says

Glynn,

This is such a needed and important post.

It explains so much and has increased my knowledge of and appreciation for the Fireside Poets.

Appreciate the links you provided for further reading and research.

Gratefully,

Katie