Sam Leith traces how children’s stories began and changed

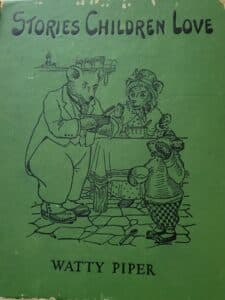

One of my earliest memories is of my mother reading to me from a big, green book of tales for children. Stories Children Love by Watty Piper, a collection of nine tales, was first published in the 1920s and reprinted in 1933. I believe my book, which I still have, was a reprint from about 1950.

The stories are familiar ones, including “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Peter Pan,” “Cinderella,” “Three Bears,” and “Jack and the Beanstalk.” The illustrations are classic 1920s.

Leith, an English journalist and literary editor of The Spectator, argues that the long history of children’s stories is, in fact, a history of storytelling in general; men and women didn’t sit around campfires telling stories specifically for adults and stories specifically for children. Instead, they simply told stories.

It was only about the time of the late Renaissance that stories and literature took the first steps toward differentiation for adults and children. Most likely, the differentiation occurred as a reflection of Western culture’s changing understanding of and sentiments toward children. Leith traces how children’s stories developed and changed until the genre reached its Golden Age — the second half of the 19th century.

Key figures in the early years of that age were Lewis Carroll (1832-1898) and Charles Kingsley. Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures was something of a sea change, “at once hugely influential and entirely sui generis,” he says. “It’s almost impossible to overstate what strange books Alice’s Adventures and its sequel are.”

These books did at least two significant things for children’s literature. First, they created a new way of writing children’s stories; second, they made fun and silliness an end in themselves. Through that fun and silliness, Leith says, a writer could acknowledge the way a child saw the world. And Kingsley’s Water Babies was, if anything, even stranger than Carroll’s stories.

C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia was the major contribution of the 1950s. The books that followed that mirrored what was happening in the culture at large, with children’s stories veering toward science fiction and social issues for a few decades. And then came the 1990s, with a “back to the future” turn with J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter. It’s no surprise that Rowling had such a difficult time getting the first Harry Potter book published; the idea of a boy wizard and magic was rather old-fashioned and countercultural to what was then prevailing in publishers’ thinking. It would be the publisher best known for the distribution of children’s books through school clubs – Scholastic – that would take a chance on this odd story from an unknown British writer then living in Scotland.

Leith tells the story of children’s stories. It is a story, a profoundly interesting story — and he tells it well. A Haunted Wood is not only well-researched but also engagingly written.

Sam Leith

Leith’s published works include the nonfiction books Dead Pets, Sod’s Law, and You Talkin’ to Me?. He’s also published novels and a poetry collection, Our Times in Rhymes: A Prosodical Chronicle of Our Damnable Age. Before joining The Spectator, Leith worked at Punch magazine, the Daily Mail, and The Daily Telegraph.

Leith has a strong British bent in A Haunted Wood. But then, for a host of reasons, it was Britain where the transformation of childhood began, and it was British writers who transformed children’s literature globally. Simply recite some of the names: Lewis Carroll, Beatrix Potter, J.M. Barrie, A.A. Milne, Tolkien, Lewis, Rowling. And consider the characters they created who occupy permanent places in our collective mind: the girl who fell down the rabbit hole, the arch-enemy of Farmer MacGregor, the boy who could fly, the silly old bear, the hobbits, the faun man first seen by the lamppost in the snow, the boy wizard.

Yes, they are all British, but you don’t have to be British to understand them, recognize them, and put yourself in their places. Just ask your kids. Or ask that kid whose mother read stories from a big green book, stories about three bears, a little girl who meets a wolf, and a boy who climbed a beanstalk into the sky.

Photo by Phillippe Put, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Catherine Strisik and “Goat, Goddess, Moon” - September 25, 2025

Leave a Reply