Meet the Wonderful Laurie Klein

Poet Laurie Klein has a long history with Tweetspeak, not least of which is the fact that she was the first editor to ever publish a poem by our own L.L. Barkat. (Far before Tweetspeak even existed, the two met at a conference in Michigan). Over time, the writers lost touch and then eventually found each other again online. Today you might know Laurie as the beautiful podcast host for Poems to Listen By. Or perhaps you heard she has a new collection: House of 49 Doors. Even if you don’t already know Laurie, you’ll want to. She’s poetic in a deep down way.

Tweetspeak (TSP): Laurie, we’re curious. How long have you been a poet? And how did you get into the genre?

Laurie Klein (LK): Back in the era of bell bottoms and beehive updos, I took a creative writing class. While working on a degree in art, I sporadically dabbled in free verse and felt lucky to receive a poet-friend’s occasional input. After graduating I married a folk singer. For the next twenty-five years, art took a back seat to shared songwriting and performance.

In 1996 when my father died, I sank into stage IV clinical depression. Each day felt like pushing through briers, tap-rooted in issues I couldn’t face. Meds and therapy helped. Tracking my sorrow on paper made pain seem more manageable. Those early seeds of poetry resurfaced, and the brevity of expression suited my limited energy and attention span. During this time, I met poet/visual artist Susan Cowger, who patiently showed me ways to shape raw emotion into poems. For free. The learning curve was, and still is, endlessly cathartic. For the past twenty-eight years we have been devoted friends and writing partners.

Each day felt like pushing through briers, tap-rooted in issues I couldn’t face.

TSP: The theme of your latest collection—House of 49 Doors—is not an easy one. Can you tell us what led you to delve into it? And, why through poetry?

LK: Honestly? I never meant to. I had already been self-quarantined due to a very bad bug called C. diff for five months when the pandemic hit. Homebody me didn’t mind sheltering in place for a while longer. But I grew heartsick over the depth and breadth of suffering everywhere, fueled by rampant, contagious fear. Equally appalled by our nation’s hair-trigger incivility, I missed delight.

I was homesick for a once-upon-a-time place: Fowler House.

My longing coincided with a surprise invitation. When D.S. Martin, editor of my first book, requested another manuscript, I mentioned my childhood home as a possible subject. Send it on when you’re ready, he said.

Could I do this? I went back sixty years in time, mentally revisiting the premises as well as each room, scouting emotions, sensory details, echoes of old conversations. Most of all, stories. My quasi-architectural approach suggested the spine for the project. Sometimes I wrote in the voice of my preteen self, Kid Larkin; other times, Eldergirl, my present-day self. I penned soliloquies for creatures I’d known—including those that had scared me. Such fun! My writing partner, Susan, cheered me on; she also gently urged me to explore skeletons in the family closet: specifically, my role in a long-kept secret.

Once again, the compression of poetry suited my bandwidth for working with charged material. Could a group of poems shoulder the weight of memoir, the suspense of fiction? More crucially, could I present my experience in a way that would encourage others? I had to find out . . .

TSP: Your collection has an intriguing mix of the comic and the tragic. Was this purposeful, or did it somehow just emerge? How do you feel the two play together in this collection?

LK: I’m so glad you found it intriguing! It felt risky. Initially, that serio-comic mix arose organically by staying true to the characters and my memories. Kid Larkin is easily dazzled, fierce, mischievous, often bewildered. Sometimes valiant, other times, sad. (Turns out I was also homesick for misplaced parts of myself that still had a pulse—despite being shelved for six decades.)

As the darker poems took shape, it seemed vital to strategically undercut the horror of my uncle’s suicide. Over and over, I test-drove the order by reading the whole shebang out loud, as if to an audience, monitoring my own emotional investment as well as fatigue. Where might listeners glaze over? Or bail, when things felt too intense for too long, perhaps triggering painful personal memories? I color-tabbed the pages with sticky notes, shuffling them to visually balance the moods as well as the voices, both human and creaturely.

Does the mix work? Well, innocence carries nuance. Lightheartedness as well as grief often bear powerful subtext. Unlocking and blending both aspects reflects life. Moments of well-placed whimsy also slow full revelation of the secret, creating suspense. Like most households, ours brimmed with darkness and light, trouble and unpredictable charm.

Moments of well-placed whimsy also slow full revelation of the secret, creating suspense. Like most households, ours brimmed with darkness and light, trouble and unpredictable charm.

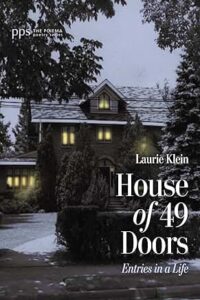

TSP: We love the title House of 49 Doors. Tell us more about it.

LK: Begin with a mom: a devout woman in a small town, known for her generosity, sacrificial care, creativity, and meekness. My mom. Here’s how I picture her breakout moment: one day, on our front porch, she stared down my often-formidable dad, her slender hands gripping a brush and a gallon of turquoise paint.

He caved.

Our turquoise front door was the talk of our 1950s neighborhood. It was big, bold, and so not June Cleaver. To this day, high school friends mention it. The midcentury cover photo on the book was taken by our neighbor before we moved in. My sister found it, scanned it, and I sent it to the publisher as a potential visual reference. Had I known in time they would use the photo, adding that welcoming glow to the windows, I would have requested a turquoise tint.

As to the number: I’d been writing for a couple weeks when, on a whim, I mentally counted up all the doors. Forty-nine? My total included closets but no cupboards. I called my sister. Curious, she counted them, too, then called me back. Her tally agreed.

Doors are so evocative. Ever since Nancy Drew (and I) discovered “the secret in the old attic,” I have adored mysteries set in old, atmospheric houses. Living in one was amazing. I hope readers entering my story will find some aspect akin to their own comings and goings. Skeletons in closets and long-neglected emotional wounds deserve loving attention, which opens the way for peace, healing, reconciliation.

TSP: Do you have a favorite poem from the collection? Will you be reading it for the Buoyancies series? (Feel free to share the whole poem or excerpts of it right here 🙂 )

LK: Here’s one from the “Buoyancies” series:

Maybe the dead leave us

a gift we cannot

imagine, moving

like water around reeds,

under an oil slick—

a current that blurs

memory’s suspect alchemy

with all the goodbyes

yet to be said, between

their death, and ours.

Picture a portage through time,

where we can un-shoulder

our past and reemerge

carried. Maybe this is how

we reclaim our lives: as if

trust is the next vessel.

TSP: Are you working on any other collections at the moment? Or would that remain as your little secret?

LK: Well, if curating a lifetime of collections qualifies, then yes. Completing the book helped me begin putting my spiritual house in order. Now, for the actual rooms I live in . . .

Photo by Nataliya Melnychuk, Creative Commons, via Unsplash.

- Poetry Prompt: Gathering Flowers - June 16, 2025

- Poetry Prompt: The Phoenix - May 26, 2025

- 10 Ways to Help Your Favorite Introverted Author: 1,000 Words - May 23, 2025

Bethany R. says

So much in this interview to glean from and respond to. But I just have to say, I love your parenthetical here. “Turns out I was also homesick for misplaced parts of myself that still had a pulse…” What a time of discovery. Thank you for sharing this and the amazing collection with the world.