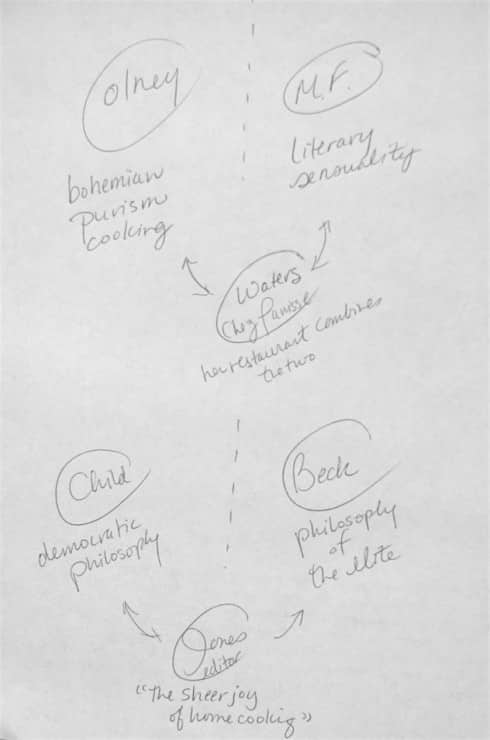

Our dear community member, Katie B. (thank you!), commented on our last Provence post, regarding how many differences the friends in Provence brought to the kitchen—and to their places in the food scene at large.

They brought differences in cooking style and philosophy. They brought differences of culture and language. One friend (James Beard) would talk endlessly with a housewife about macaroons, while another (Olney) would rather (also quite endlessly) talk French wine with an accomplished writer.

To be human is to be divided by our differences, sometimes. To be visionary is, sometimes, to bridge those divides, or synthesize them into something wholly surprising, fresh, or, if you are Alice Waters of Chez Panisse, even delectable (not to mention, good for the earth).

While we were still in the middle section of Provence, we were in the thick of the multiple ways this little community of friends and acquaintances was different. Towards the end of the book, as they each find their niche and, in some cases, stop feeling the need to prove themselves, we find them more charitable with one another.

Julia moves on to democratize cooking more than ever (she believed anyone could cook, if they were given the means) and is happy for Beck as Beck finishes up her own unique cookbook; Olney gives cooking demonstrations in America (and comes in contact with those “ordinary” people who had been empowered by the likes of Beard and Child). It is Barr’s description of Olney that most succinctly describes the shift from focusing just on differences to showing respect and maybe even feeling gratitude:

Olney had always felt on edge on such occasions [amidst the established cooking friends set], embittered and superior. But now he had a different perspective. He could see, for one thing, what an enormous impact Child had managed to achieve….The sheer numbers of people; the interest in cooking, in baking bread, in new recipes and cookbooks, owed much to her, and Beard’s, pioneering work.”

—p. 252

More touching, we see Olney’s brothers, hours after his death, “eating the last meal Richard will ever cook for us” and Child remarking that she would give up the house at La Pitchoune, because “without Paul to share the house with, or my grande chérie Simca [Beck]…it had come time to relinquish La Pitchoune.”

In these moments, we understand quite deeply what editor Judith Jones had known, more deeply than anyone: that these chefs and writers, with all their differences, also held something powerful in common—”the sheer joy of home cooking” in which “there is love and care that is expressed in cooking for someone else.” (p. 264)

We could learn much from this recipe.

***

We’ve been reading Provence, 1970 together this month. Are you reading along? This week we wrap up our discussion with Chapters 13-17. Share with us in the comments what you think so far. What images have stirred? And what dish are you now eager to prepare (or order in)?

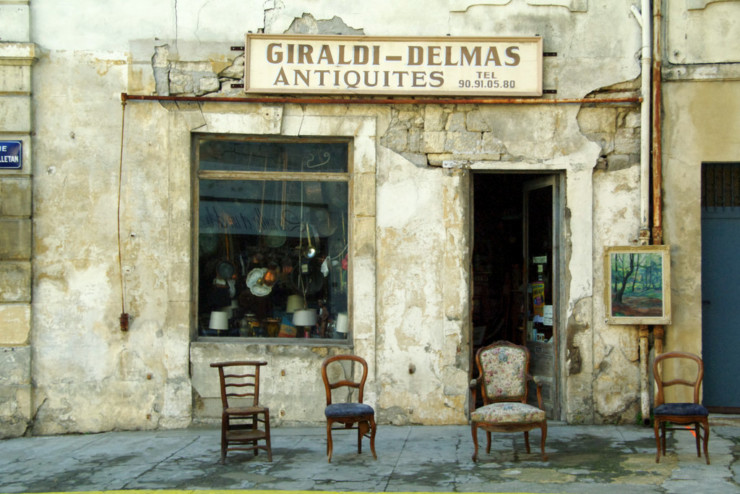

Photo by vasse nicolas,antoine, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by L.L. Barkat.

Reading Schedule:

Announcement Post

August 8: Chapters 1-6

August 15: Chapters 7-12

August 22: Chapters 13-17

Buy Provence, 1970

- Learning by Poetry: C’est Fait Par du Monde - November 10, 2025

- Learning by Poetry: Pas du Tout - October 8, 2025

- Found in Translation: Gently May It Sing - September 15, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

I think what spoke to me most was the need for change each (almost each) person was feeling and how that change would affect the others.

And still the hunger…

On page 187: “It’s not the weather that stymies me,” she [M.F.} wrote to Gingrich, describing the persistent cold and bitter wind, “but that I’m HUNGRY.”

It was a physical hunger, but more. She went on to write about past Christmases in different places, “But then I was with people I loved. Now I am alone, and it is RIDIKLUS to be alone and hungry at the same time.”

And then… “She felt guilty for leaving, but why would she? In fact, now that she had decided to go, she felt suddenly confident . . . She felt in control. She was hungrier.” – Page 188

Later Barr writes that M.F realized she missed her family and being near people she loved. She was cold. It was like a shift when the fountain froze. How cool was that image?

I think that’s how it is when we start changing and feeling the need for change. There’s that deep hunger and maybe guilt and then and wondering how decisions will affect others… and then, once we make the decision, there’s a sense of control and maybe a feeling of being “sated and happy.” ~ Page 194

On page 220: “And so 1971 began: cold, stormy, and with low visibility. It was a year of new beginnings,” also the title of chapter 17. That was the year I got married. So I started to compare what was happening in my life with what was going on in these friends’ lives at the same time. (I, by the way, have a very tattered “The Vegetarian Epicure” that I pulled back out again. It’s mentioned on page 240.)

I found that scene with the brothers “eating the last meal Richard will ever cook for us” so touching. And the trip Barr took back to Provence with Norah (in her 90s!) in 2010–all the changes… box stores, car dealerships, crowded roads, the hunt for local food shops… made me sad. But the knives in Julia’s kitchen were still very sharp, and Paul’s instruction book for guests still remains and made me laugh. (There was a book like that in the cottage we rented in Pompano Beach when we first moved here.)

But “The shift that had occurred in the fall and winter of 1970, when Child, M.F., Beard, Beck and Olney had come together, finding new directions for themselves and for American cooking, lived on, too.” – P 285

And then that last meal… with an “eye on the past” and the remaking of the legacy in the present. And the last paragraph, what M.F. had written to Child, “There is all the imprisonment of nostalgia, but with so many wide windows.”

Recipes? Not all those birds and wild things on their menus. Maybe Mme. Gatti’s long-lost lemon tart. I was kind of partial to the bread and cheese. And wasn’t that image of Julia “de-tendoning” a goose on page 201 hysterical? And the boiled English chicken on page 204?

L.L. Barkat says

I love all these quotes you’ve pieced together. Your own journey within Provence’s pages (the fountain was one of my favorites, too, and the champagne which was cold and still lively… these images had an interesting effect when we usually consider cold things to be non-growth images, but in this case they seemed to hold the strangest kind of hope. Her life was not over. It was just going to be different, and alive in a new way.

The wild things. I’d like to leave them with Sendak ;-). The English chicken was hysterical, in an understated way.

I, too, loved the “so many wide windows.” They are going to stay with me. 🙂

Laurie Klein says

Sandi, this:

“I think that’s how it is when we start changing and feeling the need for change. There’s that deep hunger and maybe guilt and then and wondering how decisions will affect others… and then, once we make the decision, there’s a sense of control and maybe a feeling of being “sated and happy.”

You’re speaking hope into my life, girlfriend, via

restive hunger … guilt … worry … release to move ahead and the relief (perhaps, joy?) it brings.

Thank you.

Laurie Klein says

LL,

What complex cookery, camaraderie, competitiveness, and connections.

Their communion.

Their Last Supper.

And the savory role of editor as visionary and artisan, companion to the writer and work for the welcoming sake of the extended table and all who will feast thereon . . .

Katie says

Sandi, L.L. and Laurie,

Wonderful discussion here:

Your keen observations on Provence (never found my later notes – think I inadvertently discarded them:(

SO much I’d like to respond to, especially Chez Panisse. Thank you for that link L.L. – what a fascinating restaurant.

I like how Richard Olney and Elizabeth David’s writing influenced the menu.

Also, that when Alice Waters visited France what appealed to her were not the fancy restaurants but the places where cooking was simpler and celebrated the local produce.

Here in MD, we are soon to have a “farm-to-table” restaurant opening in a town close by. I’m looking forward to eating there and tasting the freshness of the Southern Maryland Harvest:)

L.L. I love how you brought this all around and distilled wisdom from the quests these food writers were living in and through their careers and lives.

“In these moments, we understand quite deeply what editor Judith Jones had known, . . .that these chefs and writers, with all their differences, also held something powerful in common – ‘the sheer joy of home cooking’ in which ‘there is love and care that is expressed in cooking for someone else.” (p. 264)

INDEED, we could learn much from this recipe! (your terrific diagram – helped me review this group and glean even more appreciation for their styles)

“To be human is to be divided by our differences, sometimes. To be visionary is, sometimes, to bridge those divides, or synthesize them into something wholly surprising, fresh, or if you are Alice Waters of Chez Panisse, even delectable (not to mention good for the earth).”

Katie says

L.L.

Thanks again for your post – I tried my hand at some Black Out Poetry with it:

More Than Just Different

differences in cooking

style and philosophy

differences in culture and language

to be human is to be

divided in our differences

to be visionary is to bridge those divides

shift from focus on differences

to showing respect and gratitude

with all their differences

they held something powerful in common

the sheer joy of home cooking

in which there is love and care

that is expressed in cooking for someone else.

L.L. Barkat says

Thank you so much, Katie! This feels a little more like a “based on” poem than a blackout poem (which would keep all the original words and syntax).

I like how you pulled upward the little scaffolds of the original piece. Gratitude takes an awful lot of vision, doesn’t it?— especially gratitude for those who’ve done important things in ways that build us, even as we find it hard to connect with the builders.

Katie says

Thank you, L.L.:)

This book reinforced to me the reality that we each have different gifts and skills to offer. Would that we would look for and champion one another’s abilities and contributions.

The TSP community does this quite well.

Gratefully,

Katie