Here’s what we know so far:

One: France can be a cold place.

Two: Sharing the wrong kind of details about preparing a delectable French meal may leave your reader wanting to go to bed without their supper.

Three: Sometimes your friends are people with edges.

Let’s take them in order.

France can be a bit chilly. Browse the weather reports, and yes, you’ll see that despite appearances, even in the south of France where maybe we’d like to think that a Mediterranean climate means that it’s sunny and warm and northern California all year round, the winters are cool. But don’t get hung up on the weather—that’s not what I’m talking about. I mean—at least, this is what I hear—if you’re an American used to a lot of doting, hands-on attention from service workers, France might feel a little on the nippy side.

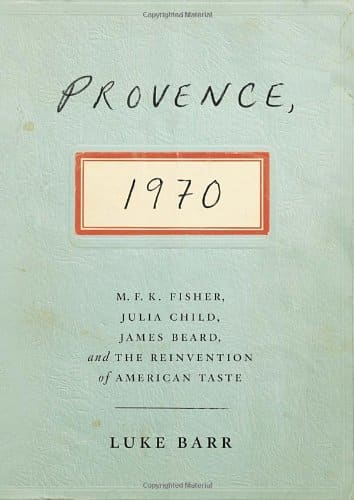

This is something of the experience M.F.K. Fisher encounters during that winter of Provence, 1970, when she arrived at a hotel in Arles in the off season. Her great-nephew Luke Barr, who wrote the tale based on Fisher’s letters and journals, describes the scene in which she found herself:

She made her way to the front desk to check in. The decor was Provençal rustic, almost cliché, with tiled floors and wrought-iron chandeliers. She’d been here years ago, and it hadn’t changed a bit. Her heels made echoing noises in the empty lobby. It was the week before Christmas 1970, and the weather was unusually cold. She had the distinct impression of being the only guest at the hotel. The place was a tomb.

The tall man at the front desk was vaguely hostile. He was sullen, but then that seemed to be the default posture of French service personnel in general, at least when it came to Americans during the off season. Veiled contempt. He explained that the room she had written ahead to request—one facing the Place du Forum—would be too cold at this time of year. He did not apologize for the lack of heat, he simply stated it as a fact.

This was not M.F.K. Fisher’s first French rodeo. She’d been to France plenty of times. In fact, as Barr writes, she’d been to this very hotel before. It strikes one as something to which she should already be accustomed, and perhaps not require the repeated mental cursing of the desk clerk, and other individuals who did not trip over themselves (or even look up) to attend to her needs. Though one could also argue, as Barr seems to, that this silent cursing was in fact her long seasoned response after a lifetime of such encounters.

As the story is told, “The town was closed for the season. fermeture annuelle, read the signs on every restaurant, including, most unforgivably, the restaurant and bar in her own hotel. The tall and less-than-friendly front desk clerk told her this without looking up.”

She cursed him in her mind. “This occurred with some frequency: she would swear to herself, fuming at an irritation while outwardly maintaining an air of dignified, steely calm. There was the man at the American Express ticket counter in Cannes this morning, for example, who had issued her a ticket for a nonexistent train to Arles. She’d returned to the office, and he had impassively explained that she was surely wrong, then looked at the schedule and discovered he was wrong and blandly handed her back the ticket and said she could take the next train, in a few hours. ‘Too bad,’ he said, diffidently.”

She cursed him, quite thoroughly, quite silently.

Describing your food might be more worse than playing with it. In the setup to the gathering of this collection of storied culinary icons—Fisher, along with Julia Child and her husband, Paul, Child’s co-author Simone Beck, Knopf editor Judith Jones, and chefs James Beard and Richard Olney—Barr tells the story of Fisher and her sister, Norah Barr, joining writers and longtime friends Eda Lord and Sybille Bedford at the home of Olney, a friend of Lord’s that she was eager for Fisher to meet.

Olney, before their arrival, spent hours (maybe we should say days) in preparation. Barr takes pains to describe the work of this flamboyant, and as kitchens go, meticulous character.

He was alone in the kitchen. He was happiest at moments like this.

Now he took on the terrine, a delicate operation. Laid out on the counter were were two sole and large bag of small sea urchins, all from the fishmonger in Toulon. The sea urchins were still alive, their black spines moving. He filleted the fish, and started a stock with the bones, pouring over water and wine. It would cook for hours, until it had thickened to a jelly-like substance he would use to coat the terrine the next day.

He used scissors to open up dozens of sea urchins, holding the sharp, spiny shells in a folded dish towel to avoid injury to himself, and spooning out the pungent and slightly spongy roe inside. They smelled of the ocean. He combined the vivid orange roe with a small amount of uncooked, chopped white fish, then pushed the mixture through a fine sieve, one tablespoon at a time. These were the first ingredients in what would become a mousseline, a very delicate foamlike mousse that would be surrounded by the sole fillets.

I googled images of sea urchins, terrine, and roe, hoping to settle my stomach. It wasn’t a good idea. I thought about cursing at Olney, silently.

Friend is a funny word. Once we have Barr’s prologue out of the way, the book opens with Fisher’s trip to the cold, off-season Arles in December. As we discover in Chapter 2, this was 10 weeks after her visit to Olney and his little black sea urchin spines. The group had all arrived for the fall.

During the late fall and winter of 1970, they all lived together as neighbors in the most beautiful place in the world. Provence was where it had all started. It was a place that epitomized the food-centered culture and philosophy the group stood for, a place where life and cooking and style all intertwined so easily. The farmers’ markets, the heat and sun and abundance all around, the wild and slightly disheveled gardens and fantastic sproutings of rosemary, thyme, and lavender. The elegant but simple outdoor entertaining. The old tumbledown farmhouses.

Provence was also the place, not coincidentally, where American cooking would first break with France, where its modern character would begin to reveal itself.

We read of a growing dissatisfaction in Child’s relationship with Beck. As though setting the stage for some later falling out (who knows, really, I haven’t read that far), Barr notes that Fisher and the Childs didn’t know each other all that well. Fisher does take an immediate liking to Olney when they meet, and yet Barr writes that it was meeting Olney that “spurred her sudden departure” from this “mostly pleasant company of family and friends.” When we find Fisher in Arles, she “was eager to get away and be on her own.”

This may change as the story goes on. For the moment, it seems Fisher considers her friends to be people to be away from. Even so, she is sullen, thinking back to the warmth of these other times, mystified that she is “hungry and alone in France of all places.” And she is finding nothing but things to curse at wherever she finds to look.

***

We’re reading Provence, 1970 together this month. Are you reading along? This week we read the Prologue and Chapters 1-6. Share with us in the comments what you think so far. What images have stirred? Without sharing spoilers if you’ve read further on, what do you think this journey of Fisher’s will reveal? And what dish are you now eager to prepare (or order in)?

Photo by Ming-yen Hsu, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Will Willingham

Reading Schedule:

Announcement Post

August 8: Chapters 1-6

August 15: Chapters 7-12

August 22: Chapters 13-17

Buy Provence, 1970

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

Sandra Heska King says

I’ve taken the time to read these first chapters. Here are some notes I took.

This lifestyle does not compute–but I’d like to go to France.

The conversation seems so superficial — almost judging, snobbish. Are these people *really* friends?

“She noticed in herself a growing impatience for this sort of talk, for the rarified and studiously opinionated banter about wine pairings and menu design, which at some level to her ear, always ended up sounding self-congratulatory.”

Writing and publishing and promoting these cookbooks was a VERY BIG deal.

“For MF, was the viability of the literary voice and persona she had cultivated for nearly four decades.”

I would not have the patience to wade through 24 pages and 54 drawings to make a loaf of French bread. Publix, here I come.

“She could feel the past slipping away. She wasn’t quite sure what she wanted for the future.”

“Here she was, the great chronicler of food and love, of appetite and longing, hungry and alone.”

Seems fitting that France is cold and that she is struggling to find food. “There she had been, in the hills above Cannes, surrounded by warmth, friends, and sustenance, and here she was in Arles, cold and alone.” And hungry. I’m not sure she was particularly warm or sustained with her friends.

There was a lot of letter writing happening.

Something was shifting…

The three women decided to do a potluck in response to Olney’s extravaganza… “They would be hospitable in their own communal, casual way–creating a meal far less elaborate…” Works for me.

MF contemplated a simple dinner: a lamb’s lettuce salad, bread, and cheese. (Yes, please.)

I appreciate the artistry needed to create such beautiful food. I did very much like the attention paid to the descriptive writing of the food–though the urchins made me squeamish.

“We can try to reach the slower pace of older habits than our own new nervous ones,” MF had written. And then she wrote to Julia, “…we both understand the acceptance of NOW. There is all the imprisonment of nostalgia, but with so many wide windows.”

MF seems to be feeling some emptiness in this lifestyle.

I think I would have liked Julia Child.

L.L. Barkat says

Sandra, I love the quotes you pulled out and added to what LW offered as a starter. Also, I am juxtaposing them with some quotes from the Prologue, which has some odd juxtapostions itself… the “open kitchen” versus the cat “never friendly” who would “retreat stiffly out of sight.”

There is, I agree, a sense of something in-between-ish going on with MFK. In a way, maybe that was part of who she was: “She looked me right in the eyes and listened when I [as a child] spoke, and in her eyes I saw an impossible combination of intense interest and dispassionate, calculating judgment.”

I wonder if she was coming up against even herself in the opening scenes that follow her nephew’s prologue. Actually, I shouldn’t really wonder. He does say, “It was a journey that would challenge many of her beliefs about herself, and about France, which she had loved for so many years.”

In this way, it feels like the friends and all that was going on with them, becomes a backdrop for the heart—hers. And then, more than a backdrop… a driving force (like a chilly wind that pushes you to move on).

I do love the way the book captures this feeling of being alien in your own skin and in places that should be familiar but are somehow no longer familiar.

Overall, it’s not like I feel I can understand their world of fame and competition and foreign travel, yet I do feel I can understand the in-betweenness—something that transcends social and geographic situation. And I just love the way food is something we can welcome with (and we see how it can also be used to alienate, though that alienation can also be accidental).

A side note on Olney. I think sometimes we only consider friendship to be that warm fuzzy thing that makes us happy within ourselves and with each other. But perhaps there is that place for the friend with edges—the one whose “sharp-edged angular personality would bring underlying conflicts to the surface”; we don’t have to give our deepest hearts to such a friend, but we could, perhaps, see how vital they are to our wholeness (individual and communal), in their particular role.

So many more things to say about this story. I’ll stop and listen to what others may have found. 🙂

Will Willingham says

Part of the challenge for me in this reading is not really knowing these (rather famous) characters very well in the first place, so trying to work out who they are. Barr does a good job of letting the reader see them, but there’s still a fair bit that seems assumed, though I’m not sure what the assumptions are meant to be. So it makes it harder for me to understand what’s going on with Fisher, though clearly there is something that has left her so at odds with otherwise, for her, beloved surroundings. I’m interested to see how this develops.

Sandra, yes, 24 pages on bread… I’ve baked my share of bread (I enjoy it more than a person might expect) but I don’t have the staying power to follow that extensive of directions. I used to have a bread cookbook from James Beard (Beard on Bread, I believe it was called) and I think it was far simpler than Child’s 24 pages, though she’s the one that is credited with making such cooking attainable. (Is it any wonder I’m having trouble keeping track of these people.)

Debra Hale-Shelton says

I’ve been debating which food literature book to read next? I just saw this post and comments and plan to dive into Provence, 1970 tonight. Thank you!

Will Willingham says

So glad this fit the bill, so to speak. 🙂 Look forward to hearing your thoughts as you read. 🙂