Stephen Foster was America’s first professional songwriter

You can’t research and write a novel about the Civil War, or anything else set in the mid-19th century, without quickly running into the songs people sang. As I researched what would eventually become my novel Brookhaven, I came across war songs, anthems, songs sung by the Irish who came to America and enlisted, songs by the home folk, hymns, and more.

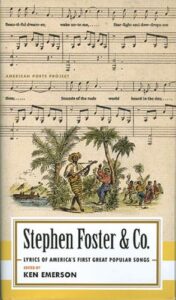

I went looking for a book about music in the Civil War, and I found a small volume published by the Library of America in 2010, Stephen Foster & Co.: Lyrics of America’s First Great Popular Songs. It’s a small, eye-opening gem. I discovered that songs I learned in elementary school had been around for more than a century.

His music is associated with the Old South, even though he was born in Pittsburgh, lived his entire life in the North, and visited anything further South than Kentucky only once. And yet he wrote “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Away Down South,” “Camptown Races,” “Old Folks at Home” (”Way down upon the Swanee river…”), and a host of other songs about the South. Like this one:

Susanna

I come from Alabama with my banjo on my knee

I’m going to Louisana my true love for to see.

It rained all night the day I left, the weather it was dry

The sun so hot I froze to death, Susanna don’t you cry.

Oh! Susanna, do not cry for me;

I come from Alabama with my banjo on my knee.

I’ve included text as I learned it in school. Emerson uses the original text in the book, which spells the words like Foster imagined slave dialect to sound. Emerson explains in his introduction that Foster’s lyrics would have been sung as expected for almost any southern or northern audience in the mid-19th century. Today, we would understand many of them to be written in racist terms.

Not all of Foster’s songs were about the old plantation South. He wrote parlor songs like “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” and “Beautiful Dreamer,” protest songs, and war songs. Foster wrote some 200 songs in all, of which Emerson includes 32 in the book. He also includes songs by others who are little remembered today, like Will Hays, W.W. Fosdick, James Bland, Henry Clay Work, and several others.

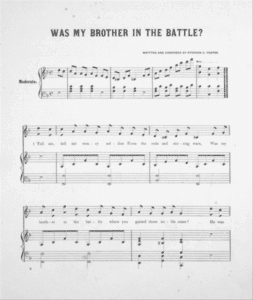

One of the most poignant of Foster’s songs in the book is a war song written in 1862: “Was My Brother in the Battle?”, about a man searching for news of a brother feared dead.

Was my brother in the battle where you gained those noble scars?

He was ever brave and valiant, and I know he never fled

Was his name among the wounded or numbered with the dead?

Was my brother in the battle when the tide of war ran high?

You would know him in a thousand by his dark and flashing eye

Chorus:

Tell me, tell me, weary soldier, will he never come again

Did he suffer ’mid the wounded, did he die among the slain?

Was my brother in the battle when the noble Highland host

Were so wrongfully outnumbered on the Carolina coast?

Did he struggle for the Union ’mid the thunder and the rain

Till he fell among the brave upon a bleak Virginia plain?

Oh, I’m sure that he was dauntless and his courage ne’er would lag

While contending for the honor of our dear and cherished flag

(Chorus)

Was my brother in the battle when the flag of Erin came

To the rescue of our banner and protection of our fame

While the fleet from off the waters poured out terror and dismay

Till the bold and erring foe fell like leaves on Autumn day?

When the bugle called to battle and the cannon deeply roared

Oh! I wish I could have seen him draw his sharp and shining sword

(Chorus)

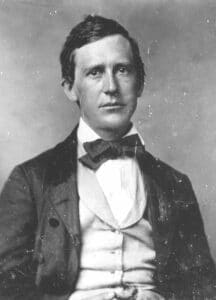

Stephen Foster

Foster’s influence on songwriters (and scriptwriters) continues today. His lyrics were embraced, modified, edited, cited, and used by such composers as Irving Berlin and George Gershwin. Emerson notes in his introduction that Bob Dylan recorded his own version of Foster’s “Hard Times Come Again No More.”

One of my favorite episodes of the 1980s television sitcom Mork and Mindy had Robin Williams (the alien Mork) singing “Camptown Races Nine Miles Long, Nan-noo, Nan-noo.” And Foster’s songs have been recorded by Nelson Eddy, Bing Crosby, Ray Charles, the Sons of the Pioneers with Roy Rogers, James Taylor, Bruce Springsteen, and Mary Blige, among others. Seven of his songs were included in the movie Gone With the Wind (all uncredited).

Despite his songwriting success, Foster struggled financially his entire career. He died at age 37 in 1864; chronic alcoholism contributed to if not caused his death. His fame, and his songs, long outlived him. And his songs opened a door on American history, culture, and the Civil War.

Photo by Nicki Varkevisser, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poet Sidney Lanier and the Lost Cause - October 2, 2025

- Poets and Poems: A.J. Thibault and “We Lack a Word” - September 30, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Catherine Strisik and “Goat, Goddess, Moon” - September 25, 2025

Leave a Reply