About Wendy Wisner

A contributing writer at Verywell, Care.com, Parents.com, and Health.com, Wendy Wisner is a freelance journalist and content marketing writer. She has published hundreds of articles and essays in places like The Washington Post, VICE, Family Circle, Parents Magazine, Lilith Magazine, Rewire, Your Teen Magazine, Brain, Child Magazine, and Scary Mommy.

Prose background aside, Wisner’s first love is poetry. She has an MFA in Poetry from Hunter College, where she taught writing and literature for four years. Her poems have appeared widely in literary magazines, including Prairie Schooner, Spoon River Review, Passages North, Tar River Poetry, Nashville Review, and Minnesota Review. Winner of the 2003 Amy Award and a 2001 recipient of an Academy of American Poets prize, her work has been a finalist for several awards, including the Robert Dana Anhinga Prize for Poetry, the Cleveland State University Poetry Center Prize, the Richard Synder Memorial Prize, and the Word Works Washington Prize.

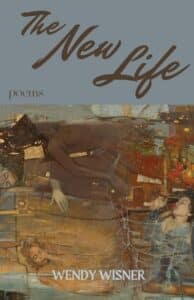

Cornerstone Press, part of the University of Wisconsin Stevens-Point, recently published Wisner’s third book of poems, The New Life. She has two previous poetry collections, Epicenter and Morph and Bloom.

Listen in on Our Chat with Wendy

Tweetspeak Poetry (TSP): Why did you choose to become a poet? (Or do you feel, somehow, it was not a choice?)

Wendy Wisner

Wendy Wisner (WW): I was always drawn to poetry. My mom used to recite Walt Whitman and Edna Vincent Millay when I was a child. One of my favorite books when I was very young was a book of fairy tales written by E.E. cummings called Fairy Tales. So it felt like poetry was a normal part of life and literature, and I was baffled by people who would say that they didn’t “get” poetry, because it made perfect sense to me—this wild, surreal, elevated, interior way of speaking about the experience of life. When I was a teen, I started reading Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, and it was like, “Whoa, there’s poetry that can speak to the experience of being a woman in a body in this world?!” That’s when I started writing poems. Most were kind of terrible, but all of it felt charged and real to me, so I kept on going. I really haven’t stopped.

TSP: You’re also a professional prose writer. How did you get started in paid writing? (Trace your path for us a little, so someone just getting started might envision a road map if they’d like to do paid writing, too.)

WW: I was an English major in college and English was always my best subject in school, including essay writing. When I became a parent, I got immersed in the breastfeeding and parenting world. I became a breastfeeding counselor and board certified lactation consultant (IBCLC). I started a breastfeeding and parenting blog in 2012, and one of the pieces was picked up by the parenting website Scary Mommy. Things kind of snowballed from there, and I started getting paid by Scary Mommy and other parenting websites to write about parenting and other related topics. Because I had a health professional background and was trained in science and health-related topics, I was able to branch out from there and pick up work as a general health and wellness writer. That’s what I do today—I write health and parenting articles for various outlets. It’s my full-time job, and I love it because I get paid to write, I’m always learning, and I get to do it from home.

TSP: You’ve said elsewhere that you’re “a horrible traveler.” What makes travel difficult for you? What makes home the place you prefer to be?

WW: I’m working on this, and I’m somewhat of a better traveler than I was when I said that! I’m an introvert and highly sensitive person, so the sensory stimuli of traveling can just be a lot for me. I’m also a very routinized person and I don’t love when my routine gets interrupted. But a big part of this for me is that when I was a child, we moved around a lot. My parents were hippie/activists and also were constantly breaking up and getting back together. We moved around 13 times by the time I was 13 years old. I went to six different elementary schools. So travel and moving are all a little triggering for me, because they feel like serious instability. I think people react differently to moving around a lot, but that’s how I’ve reacted. Again, I’m trying to work on this, because I often get something deeply nourishing out of traveling.

TSP: You’ve also said elsewhere, “I still feel like my life doesn’t really mean anything unless I made art out of it.” Could you say more about that?

WW: Poetry feels like a way to capture the impermanence of life. It’s a way to make meaning of the small, ordinary moments of life—and of course, to process the painful moments. I think most poets and writers look at life and think about how they are going to record it in some way. We are record-keepers, the witnesses. This is a constant thing for me. It’s how I get through difficult times, and it’s how I try to savor the beauty.

TSP: What skills or qualities do you think are most important for being a poet? Are there any special experiences or training you’d recommend for beginning poets?

WW: If you want to be a poet, you should read poems. As many as you can get your hands on. Poems that speak to you, and poems that feel strange or hard to understand. I think we learn so much from reading different voices, styles, and sinking our teeth into the different ways poets craft their poems. When possible, I think it can be incredibly helpful to study with a good teacher or mentor, whether formally or informally. I’ve had several mentors over the years, in college, grad school, and through connections I’ve made in the poetry world. There’s no one “right” way to do it, but I would say to study and read poems and to connect with other poets/teachers/mentors.

TSP: We noticed an interview with you called “letting myself make less sense.” What a wonderful gift to give yourself. What started you on this aim? How are you cultivating a “make less sense” process?

WW: There are times when I write pretty narrative poems, and I think there’s value in that. But I also find that poems that don’t always make sense and aren’t exactly linear—where the language comes from deep in the subconscious—are incredibly moving. I think the best writing is writing that takes risks, and where the poem and the language of the poem comes from a place of “making less sense”—a place of instinct and intuition. Sometimes I have to consciously “go there” in order to write the poems I want to write. This is especially true since I became a prose writer for work. Writing health and parenting articles is very different from writing poetry. So “letting myself make less sense” is almost a way of inviting myself into the mind-space of poetry.

Try It: Make Less Sense Prompt

We love the way Wendy Wisner deliberately takes the risk of “making less sense” in her poems, calling on instinct and intuition in the process. In a poem you title either “Instinct” or “Intuition,” try making less sense as you concurrently take some risks. Let your language come from your subconscious. How to get there? Try doing some rapid word associations for 10 minutes before you begin your poem.

Photo by Jr Korpa, Unsplash license.

- Poetry Prompt: Gathering Flowers - June 16, 2025

- Poetry Prompt: The Phoenix - May 26, 2025

- 10 Ways to Help Your Favorite Introverted Author: 1,000 Words - May 23, 2025

Donna J Hilbert says

Yes, to make less sense. The unconscious mind often knows best.

L.L. Barkat says

That sounds like the beginning of a poem of its own, Donna! 🙂

Bethany R. says

percolator clicks

On. morning thoughts instant fever

rest your hand

on the Peace Lily’s leaf

after days of garage-darkness and absolutely no water

here it is

now back by your bed

palm pause

cool press

cellular respiration

the leaf against your cheek

how quiet you’ve become

Bethany Rohde says

I love these poet interviews! I’m thinking about what Wendy Wisner says here. “But I also find that poems that don’t always make sense and aren’t exactly linear—where the language comes from deep in the subconscious—are incredibly moving.”

Intriguing. Maybe that is another reason I’m so drawn to writing found poetry these days. It provides a way to locate and push up a different type of vernacular and idea than I normally find in myself. But it’s still me doing the arranging and choosing. I’m designing a quilt with someone else’s squares.

Hm. When I actually think about being in the middle of that process, I feel both focused and in a bit of a dreamy-state(?) while piecing a found poem together. Ultimately, I want the finished draft to be accessible to the reader, but I think my gut instinct plays a large role. Fun to experiment here with free verse.