Leonardo and Sfumato

It’s not that I don’t think the Mona Lisa is beautiful.

I suppose I actually do. It’s more that I just don’t find her all that attractive.

I would not, probably, ask her out on a date. And that’s not just because she’s not alive.

There is something mildly unnerving about her. I can say that now — mildly unnerving — because I am a grownup, and I’m able to remind myself that she’s a painting, not a person with flesh and blood. As a child, I found her to be far more than unnerving. She frightened me. That strange quality of her eyes that followed a person around the room. (I don’t actually know if that was a real thing, or if that was a Scooby Doo cartoon holdover. Either way, it had a lasting impression.) Her smirk, like she knew something important, even something dangerous, but preferred her own amusement more to your safety. Her cool demeanor, hands calmly folded at her lap, unflapped in the face of whatever peril might await you.

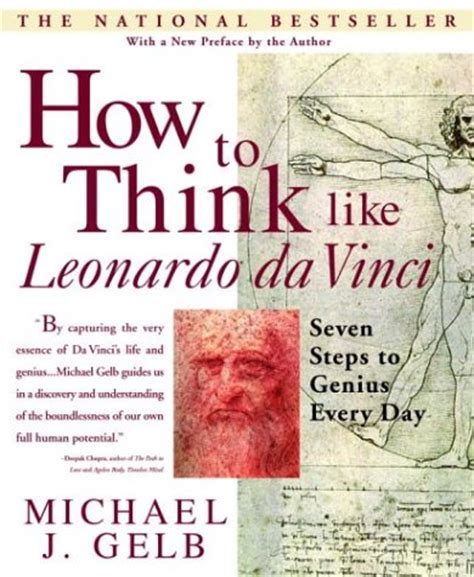

It is possible that my childhood discomfort and adult ambivalence toward the lovely Mona Lisa have roots in the same mystery that others have found in her presence. Walter Pater, a scholar of the time and of the painting, wrote that she is “a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by little cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions.” Michael Gelb, author of our book club selection How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci, says that “Mona Lisa’s smile lies on the cusp of good and evil, compassion and cruelty, seduction and innocence, the fleeting and the eternal. She is the Western equivalent of the Chinese symbol of yin and yang.” She is, Gelb writes, “Leonardo’s supreme expression of paradox.”

So perhaps it is not any unique quality of her face that is unnerving, but the very aspect of ambiguity that she, in this fleeting moment captured on da Vinci’s canvas like a Renaissance version of a Polaroid, embodies.

Gelb describes one of the qualities essential to a person who wishes to experience something of da Vinci’s genius: the painting technique of sfumato, the “essence of paradox.” He cites E. H. Gombrich, who studied the effect of this paradox in the painting, suggesting that the “blurred outline and mellowed colours … allow one form to merge with another always leaving something to our imagination.” Gombrich explains that, like any other portrait, the image’s “expression” is captured by two features: “the corners of the mouth and the corners of the eyes. Now it is precisely these parts which Leonardo has left deliberately indistinct, by letting them merge into a soft shadow. That is why we are never quite certain in what mood Mona Lisa is really looking at us.”

A person just really can’t ever know what she’s thinking.

And that, for some of us, is mildly unnerving.

Even just this week, a new study was released that argues her smile was disingenuous, with some suggesting da Vinci brilliantly did it on purpose. This ambiguity, this sense of unknowing, is a reality with which Gelb argues we must become more comfortable. “In the past, a high tolerance for ambiguity was a quality to be found only in great geniuses like Leonardo. As change accelerates, we now find that ambiguity multiplies, and illusions of certainty become more difficult to maintain. The ability to thrive with ambiguity must become part of our everyday lives. Poise in the face of paradox is a key not only to effectiveness, but to sanity in a rapidly changing world.”

Gelb writes that a path toward increased comfort with ambiguity might lie in the eyes and smile of Mona Lisa herself. “Sit with Mona for a while,” he says. “Wait for your mind to calm down and breathe in her essence. Note your responses.” To take it a step farther, you could also try on her smirk yourself. “Experiment with embodying Mona’s facial expression, especially the famous smile.” He suggests observing how you feel when you’re wearing that famous Mona Lisa smile, and then considering a question or situation that causes you anxiety and exploring whether your thinking on the question changes when you “look from Mona’s perspective.”

I still have mixed feelings about this painting, about this beautiful woman. I still don’t like the way she looks at me. But I’m going to try it. I’m going to see what happens when I smirk back at my life’s most perplexing questions.

***

Join us as we spend a few weeks reading How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci together. Next week, we’ll continue exploring some of the 7 key characteristics in Part Two.

Buy How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci

Photo by Davide Gabino. Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Will Willingham.

Browse more on creativity

Explore Sfmato (Ambiguity) in Keats

See Leonard da Vinci Artist Date

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

L.L. Barkat says

I like that idea of taking a gestural stance towards something. I realize I actually do that sometimes, but I hadn’t thought of it as an actual technique. It’s just a new way I chose at some point when I wanted to feel overall more peaceful and joyful. I tried, in quiet moments, to let a small smile play across my face. Sometimes now I even add a few eye flutters almost as a question and a statement at the same time.

Maybe this is why dance can be good for the heart and soul. We get to try things on for a time—new ways of moving and expressing. And these things help us see and feel differently, perhaps. (I should dance more! 🙂

I wonder how many men find Mona attractive. I’d never thought of her as either beautiful or attractive. Mostly I found her to be rather mischievous, but not in the playful way I prefer mischief to be 🙂

LW Willingham says

Embodying a thing seems to connect in the brain in a different way than just thinking about things. So it totally makes sense, doesn’t it?

The mischief is there, but I agree, it doesn’t seem playful. I think that’s maybe what bothered me as a kid.

Bethany R. says

What an interesting post, thanks for writing it. I totally hear you about that unsettling look (and the Scooby Doo holdover). What could it mean?

I also think this is kinda how I smile when someone’s taking my picture and I’m pooped. (See last Halloween’s pic of me as a giant strawberry after I got off work and was about to start trick-or-treating with my daughter.) Part of my face is trying, but I can’t get the whole thing there.

Was Mona over the sitting? “Let’s go, Leonardo.”

LW Willingham says

I love that. Mona’d had enough. But she was a good sport. 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

Bethany… Ha!

And can I just say what I thought of when I gazed on this painting again? She kind of looks like she just passed a little gas.

Also… we once had a lab we named Mona.

Sandra Heska King says

Back to NatGeo again… last months cover story on Leo notes the belief that he painted Lisa Gherardini. But Gelb offers other options–like composite of many women–or even a self-portrait.

I found Gelb’s commentary on the Last Supper interesting. That Leo would spend dawn-dusk days on the scaffold and then without warning would just take a break which didn’t make the prior too happy. But supposedly the prior complained to the duke who talked to Leo who is said to have persuaded the duke that “the greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less.” Gelb goes on to say that Leo told the duke it would be hard to find a model for the face of Judas–but in the end “there was always the head of the prior.”

I liked the reminders to rest and “trust your incubatory rhythms” and to listen “for the faint whispers of shy inner voices.”

We participated in a seder meal over Lent, and the leader discussed this painting–reminding us that Jesus and the disciples would have been reclining on pillows, that it was night, and that there were other discrepancies. I wonder why Leo chose to paint as he did.

I thought this was pretty interesting:

https://www.leonardodavinci.net/the-last-supper.jsp